Capri’s Dark Legend: What Ancient Rome Claimed About Tiberius—and Why the Story Still Haunts History

The Bay of Naples has always looked like a postcard. Bright water, gentle coves, and fishing boats drifting under a sun that makes everything feel harmless. It’s easy to believe that empires, like oceans, keep their violence at a distance.

Then the ships appear.

In the Roman world, an imperial vessel did more than carry soldiers. It carried authority that ordinary people couldn’t appeal, bargain with, or escape. Along Italy’s southern coast in the early first century AD, rumors followed those purple sails—rumors about “service,” about the palace, about families losing what they loved and never getting answers.

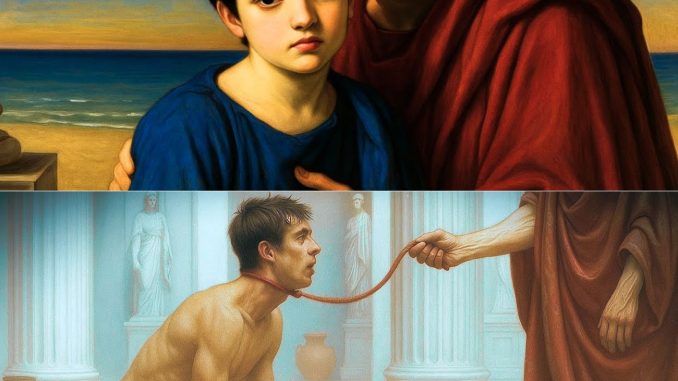

This is where one of Rome’s most unsettling legends begins: the story that Emperor Tiberius turned Capri into a sealed-off court where secrecy protected cruelty, and where the vulnerable had no voice powerful enough to be heard.

But to tell this story responsibly, we have to start with a hard truth: what we “know” about Capri comes to us through ancient writers—some sharp observers, some political moralists, and some collectors of court gossip. Their accounts are meaningful, but they are not modern court records. The darkest claims about Capri exist in a space where history, propaganda, scandal, and power collide.

The Emperor Who Left Rome Behind

Tiberius became emperor in AD 14, inheriting a state shaped by Augustus’ careful image-making and a political system that had learned to call autocracy “stability.” Tiberius was not an inexperienced ruler. By many measures, he was capable, disciplined, and feared for his competence.

And yet, several ancient sources agree on a pivotal turn: Tiberius increasingly withdrew from public life in Rome, eventually relocating much of his court activity to Capri. That physical retreat mattered more than the scenery. Rome ran on proximity—who could reach the emperor, who could influence him, who could survive his suspicion.

When a ruler moves away, power doesn’t disappear. It concentrates. It passes through gatekeepers. It hardens into a system where access becomes currency—and silence becomes a survival skill.

Why Capri Was the Perfect Fortress for a Secret Court

Capri’s geography did not create abuse, but it could enable secrecy.

The island was close enough to remain connected to governance and imperial logistics, yet separated enough to restrict who arrived, who left, and what stories traveled back to Rome. Ancient writers describe a court climate where informants, favors, and fear could thrive—conditions that make almost any scandal plausible, even before we decide what is literal truth.

This is the backbone of the Capri legend: not just “a terrible emperor,” but a place designed to keep the emperor’s private world beyond accountability.

What the Ancient Sources Actually Say (And How to Read Them)

Most modern retellings of Capri’s darkest allegations trace back to three major voices:

-

Suetonius, who wrote biographies of the Caesars and preserved many sensational anecdotes.

-

Tacitus, whose political history reads like an autopsy of imperial corruption and paranoia.

-

Cassius Dio, who compiled a vast Roman history with access to earlier traditions.

Their accounts overlap in tone more than in verifiable detail: Capri appears as a court that operated behind closed doors, surrounded by fear, and shaped by the whims of a ruler whose power had no practical limits.

But there’s an essential editorial line you should keep if you want this to be credible (and AdSense-safe): these sources report allegations and court traditions, not forensic evidence. They may reflect genuine testimony that circulated after Tiberius’ reign—but they also reflect Rome’s habit of turning unpopular rulers into moral horror stories.

That doesn’t mean “it was all fake.” It means the responsible approach is to treat Capri as a historical case study in how rumor becomes history when power blocks transparency.

The Machinery of Silence: How an Empire Buries Its Own Dirt

Even without repeating explicit claims, the logic of the story is chilling—and historically familiar:

-

Control the environment.

A remote court reduces witnesses and increases dependence on imperial staff. -

Control the narrative.

When the emperor’s inner circle benefits from silence, truth becomes professionally dangerous. -

Control the people.

In societies built on hierarchy and patronage, the vulnerable can be treated as expendable without triggering institutional consequences.

This is why the Capri legend continues to resonate. It doesn’t require supernatural elements or modern analogies. It requires only the oldest political formula in the world: unchecked power plus social silence equals harm.

What Makes Capri’s Story So Sticky Across Centuries

If Capri were just a location, it wouldn’t matter. It became symbolic because it sits at the intersection of three themes that never go away:

-

Private indulgence vs. public virtue

-

The vulnerability of the powerless

-

The tendency of states to protect reputation over truth

Rome loved moral theater. After emperors died, reputations were often rewritten—sometimes to legitimize successors, sometimes to purge a political era, sometimes because scandal sold. A “dark Capri” served as a warning: if a ruler becomes unreachable, the state can rot from within while the public is told everything is fine.

So when modern audiences read these accounts, the shock isn’t only about one emperor. It’s about the mechanism: how quickly a closed system can normalize cruelty.

The Place That Still Exists, The Truth We Can’t Fully Prove

Capri is still there. Visitors walk among ruins and reconstructed sites tied to imperial villas. The sea is still bright. The cliffs still drop into blue water. And the gap between that beauty and the accusations preserved in ancient literature creates a uniquely unsettling contrast.

But historians remain careful for a reason: the most graphic allegations in Roman biography often reflect a genre convention—stories used to signal “tyrant,” “decadence,” “moral collapse.” Sometimes those stories have roots in reality. Sometimes they are exaggerated. Sometimes they’re political weaponry.

What we can say with confidence is narrower but still powerful:

-

Tiberius did retreat from Rome for long periods, changing the politics of access.

-

Ancient writers tied his later reign to secrecy, suspicion, and fear.

-

The Capri tradition illustrates how empires can protect the powerful by isolating them from scrutiny—and how that isolation can become dangerous for everyone beneath them.

The Modern Lesson Hidden Inside an Ancient Scandal

If you strip away the sensationalism, Capri becomes a warning about systems, not just individuals.

A society that cannot question power openly will eventually lose the ability to protect the vulnerable. A court that rewards silence will attract people who are good at hiding things. A government that treats reputation as more valuable than truth will always find a way to “seal the villa,” bury the records, and move on.

That’s why Capri’s story refuses to die.

It isn’t only a rumor about Rome. It’s a pattern humanity keeps recognizing—whenever privilege meets secrecy, and nobody is allowed to say what they saw.

Sources

-

Suetonius — The Twelve Caesars

-

Tacitus — Annals

-

Cassius Dio — Roman History

-

The Cambridge Ancient History (Early Principate volumes)

-

Barbara Levick — Tiberius the Politician