Bumpy Johnson’s Final Ride and Frank Lucas’s Rise: Legend, Record, and the Harlem Vacuum

Some stories don’t survive because they’re perfectly documented. They survive because they explain a feeling: the moment a neighborhood’s balance of power tilts, and everyone senses it before anyone can prove it.

That’s why the “Bumpy died in Frank’s car” tale keeps getting retold.

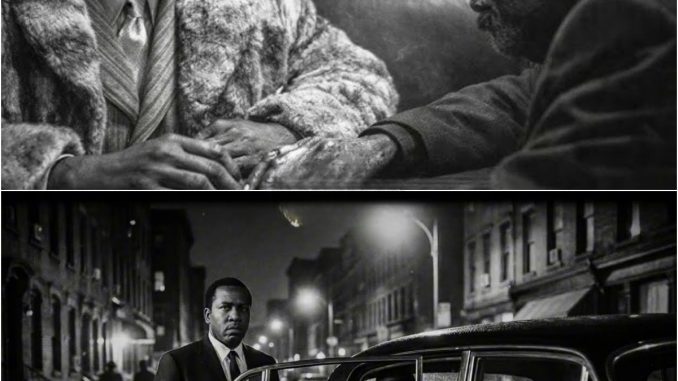

In one version, it’s intimate and cinematic: a mentor fading in a quiet car, a loyal driver trying to hold the moment together, and a few last words that feel like a crown being passed. In another version, it’s a colder truth: Bumpy Johnson’s death created a vacuum in Harlem in 1968, and Frank Lucas—already positioned nearby—had the patience and ambition to step into the space that opened.

The difference matters, because legends can blur cause and effect. If you’re building content from this story, the strongest angle isn’t to “prove” the most dramatic version. It’s to show how myths form when power changes hands—and why the community pays the price either way.

Why Bumpy Johnson mattered more than a typical crime boss

Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson is often described as a paradox: feared, strategic, deeply connected to Harlem’s street economy, yet also woven into local identity in a way outsiders rarely understand. In many retellings, he’s portrayed as a stabilizer—someone who kept certain lines from being crossed, and who negotiated with outside forces so that Harlem wasn’t simply “taken.” That’s also the basic framing behind modern dramatizations and reporting about him: his influence stretched through the 1960s until his death in 1968, and the question after that was always the same—who inherits the control he held together. (TIME)

Whether you view him as protector, exploiter, or both, the key point is structural: Harlem’s underground economy didn’t run on one man’s charisma. It ran on relationships, rules, and the ability to prevent constant fragmentation.

When that anchor disappears, the scramble begins.

The “last words” story: why it’s so sticky

The most repeated version of the handoff is morally clean: Bumpy dies, tells Frank to be careful, and Frank becomes the next king.

It’s sticky because it compresses a messy transition into a single human moment—one that feels understandable and emotionally complete. It also lets audiences believe the rise was earned through loyalty, not opportunism.

But in reality, power transfers in this world rarely happen like inheritance. They happen like markets: people test the perimeter the moment they sense weakness. Rivals probe. Former partners renegotiate. The “new boss” isn’t crowned; he’s measured.

So the best way to tell this story—without overclaiming facts—is to treat the last-words moment as the mythic symbol of a real shift: Harlem’s hierarchy was about to be rewritten, and Frank Lucas was one of the men ready to write it.

Frank Lucas as a “business story” is the most dangerous framing

A lot of modern content turns Lucas into a supply-chain genius: “cut out the middlemen,” “go to the source,” “build a pipeline,” “outsmart the system.” That framing performs well because it resembles a startup narrative.

It’s also the easiest way to accidentally glorify harm.

The more responsible (and honestly, more compelling) approach is to hold two truths at the same time:

- Yes, Lucas’s rise is often described as operationally bold—fewer intermediaries, tighter control, a brand reputation for product consistency.

- And the outcome for Harlem was not a clever case study. It was a neighborhood absorbing the fallout of a more efficient harmful market.

Even sources that summarize Lucas’s life without romantic language still emphasize that he became a major Harlem heroin figure in the early 1970s and later faced prosecution, cooperation, and long-term consequences. (The Mob Museum)

If you want this piece to feel “documentary,” the core theme isn’t “How he won.” It’s “What winning meant for everyone else.”

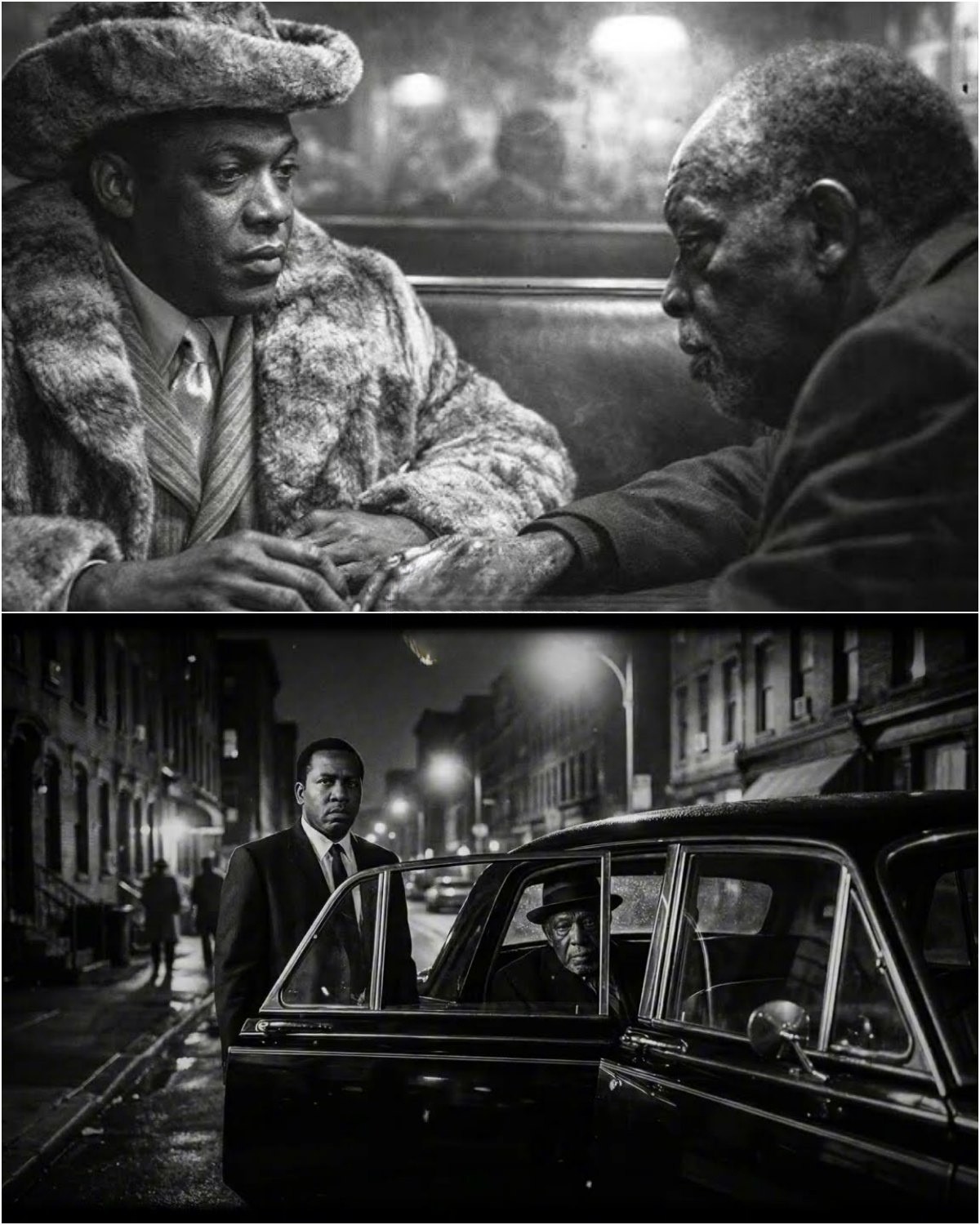

The funeral “statement” and why public theater works

One detail that often appears in retellings is the idea of a highly visible gesture after Bumpy’s death—a public “statement” meant to signal succession. Whether any specific ritual happened exactly as some versions claim, the underlying logic is real: after a power-holder dies, everyone watches for signals.

In these ecosystems, symbolism is not decoration. It’s communication.

- If you appear timid, you invite challenges.

- If you appear reckless, you invite coordinated removal.

- If you appear controlled—and backed by resources—you buy time.

That “buy time” concept is crucial. It’s not that rivals suddenly love you. It’s that you make conflict expensive enough that people pause and reassess.

The coat moment: visibility as the beginning of collapse

Many narratives include a turning point where Lucas becomes too visible—often symbolized by expensive public fashion at a famous sporting event—and that visibility helps law enforcement focus attention.

Whether that’s treated as the single cause or merely a symbol, it works because it’s psychologically true: people who run long, quiet operations survive by blending in. The moment they start performing status, they create reference points—photographs, eyewitnesses, patterns, “who is that guy and why is he sitting there?”

The documentary angle isn’t “vanity killed him.” It’s “visibility made him legible.”

The part most stories rush past: community cost

If you publish this as a long-form article or voiceover script, the most forward-looking move is to stop treating the neighborhood as set dressing.

A more grounded framing:

- A power vacuum after 1968 created instability.

- A new structure formed—more centralized, more profitable for those inside it.

- The social cost accumulated outside the inner circle: addiction, family strain, policing pressure, and a cycle of fear and distrust.

That’s not moralizing. It’s simply refusing to let the story end where the mythology wants it to end: at the “crown.”

A clean, AdSense-safe takeaway that still hits hard

You don’t need graphic detail or “hype language” for this story to land.

A strong ending is a simple thesis:

Bumpy Johnson’s death wasn’t just the end of a man—it was the end of a system of control. Frank Lucas didn’t inherit a throne so much as step into a vacuum. And the legend of “last words in a car” persists because people want transitions to feel personal, not structural—especially when the structural truth is that the community always pays first.

Sources

- Frank Lucas, the drug kingpin who inspired “American Gangster,” is dead (The Mob Museum) (The Mob Museum)

- The True Story Behind “Godfather of Harlem” (TIME) (TIME)