A Face History Could Not Erase: Remembering Aron Löwi of Auschwitz

Among the countless images that survive from the Holocaust, there are photographs that shock, photographs that document, and photographs that quietly endure. Some do not rely on graphic detail or dramatic context. They endure because they insist on recognition.

One such image belongs to Aron Löwi.

His face, preserved in an identification photograph taken at Auschwitz, has become a powerful reminder of what the Nazi system attempted—and failed—to erase: individuality, dignity, and human presence.

A Life Before the Camps

Aron Löwi was born in the late 19th century and lived most of his life in the small Polish town of Zator. He was a Jewish merchant, part of a community that had existed in the region for generations. By the time World War II began, he was in his early sixties—an age that reflected decades of ordinary human experience rather than political conflict.

He was a husband, a neighbor, a businessman, and a familiar figure within his town. Like millions of European Jews, his life before the war was not defined by ideology or resistance, but by routine, responsibility, and belonging.

That life ended not because of something he did, but because of who he was.

Deportation and Arrival

In early March 1942, Aron Löwi was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest and most lethal complex in the Nazi concentration camp system. Auschwitz had already become central to Nazi plans for the systematic persecution and destruction of Europe’s Jewish population.

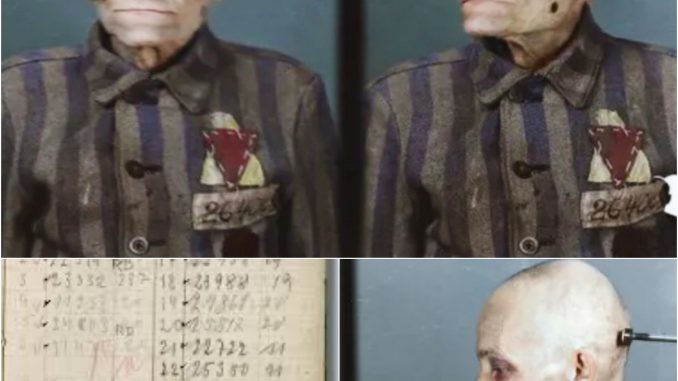

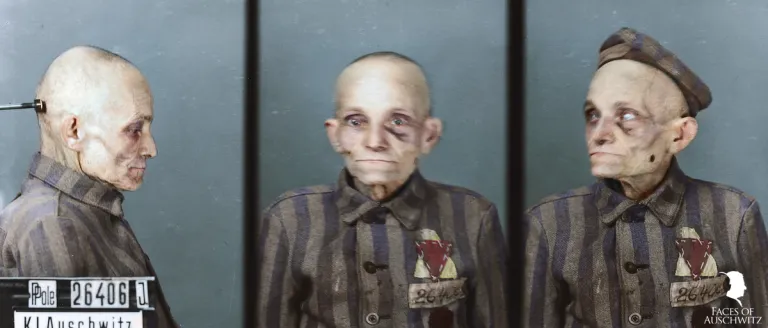

Upon arrival, Aron Löwi was registered as prisoner number 26406.

The registration process was designed to be efficient and impersonal. Names were replaced with numbers. Personal histories were excluded. Individuals became entries in administrative records. The goal was not only control, but erasure.

For Aron Löwi, that erasure lasted only days.

Historical records indicate that he survived in the camp for five days, from March 5 to March 10, 1942. There is no surviving documentation explaining the circumstances of his death. No personal testimony. No burial record.

What remains is his photograph.

The Identification Photograph

The photograph taken of Aron Löwi was part of the camp’s bureaucratic system. It was intended to catalogue prisoners, not commemorate them. Yet history has transformed its purpose.

In the image, Aron Löwi stands facing the camera. His posture is still. His expression is restrained. There is no dramatic gesture or visible defiance—only a direct, steady gaze.

That gaze has become central to how his memory endures.

The Nazi system relied heavily on visual documentation, believing that control over images meant control over narrative. But the photograph does not depict submission or anonymity. Instead, it preserves a presence that resists reduction to a number.

He does not disappear into the uniform. He remains visible.

Why Five Days Matter

From a historical perspective, five days may seem insignificant compared to years of imprisonment endured by other victims. Yet the brevity of Aron Löwi’s survival highlights a crucial reality of Auschwitz in early 1942: for many deportees, arrival meant imminent death.

Auschwitz was not only a place of long-term detention. It was also a site of immediate destruction. Elderly prisoners, in particular, faced extremely low survival chances due to the camp’s conditions and policies.

Aron Löwi’s short survival does not diminish his story. It underscores the speed with which human lives were extinguished—and how easily they could have vanished from history altogether.

Without the photograph, Aron Löwi might have remained only a number in an archive.

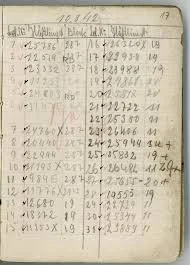

Bureaucracy and Dehumanization

The Holocaust was not carried out only through violence. It was enabled by paperwork, classification, and routine procedures. Camps like Auschwitz depended on meticulous record-keeping that transformed persecution into administration.

Prisoner cards, transport lists, and identification photographs were tools of this system. They reduced people to data points while maintaining an illusion of order.

Ironically, those same records now serve as evidence.

Institutions such as Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Yad Vashem, and the USC Shoah Foundation have worked for decades to preserve these documents—not to replicate the system that created them, but to reclaim the humanity they tried to erase.

Each preserved name interrupts the logic of anonymity.

The Power of a Single Face

Holocaust history is often conveyed through numbers: six million murdered, hundreds of camps, millions displaced. These figures are necessary, but they can overwhelm comprehension.

Individual faces restore scale.

Aron Löwi’s photograph reminds us that genocide is not only about mass destruction, but about the destruction of specific people—each with a life that mattered beyond statistics.

His face has appeared in exhibitions, educational materials, and online memorials not because it is sensational, but because it is human. Viewers often remark on the expression in his eyes: calm, awareness, and a quiet intensity that seems to cross time.

Whether or not we interpret that expression correctly is less important than the fact that it invites recognition.

Memory as an Act of Resistance

The Nazi regime sought to eliminate not only Jewish lives, but Jewish memory. Entire communities were destroyed with the expectation that they would leave no trace.

Remembrance disrupts that goal.

To speak Aron Löwi’s name today is to reverse the logic of the camp. It restores identity where the system demanded erasure. It transforms a bureaucratic artifact into a memorial.

Memory does not undo loss. But it challenges the conditions that allowed loss to occur.

In this sense, remembrance is not passive. It is an ethical act.

Beyond Aron Löwi

Aron Löwi’s story stands for countless others whose names and faces were never recorded. For every preserved photograph, there are thousands of lives known only through absence.

Many elderly victims left no visual trace at all. They were deported, killed, and buried without documentation. Their existence survives only through demographic records and the memories of those who knew them.

This imbalance makes preserved images like Aron Löwi’s all the more significant. They do not represent only one man. They point toward the millions who remain unnamed.

Why This History Still Matters

Holocaust remembrance is not solely about the past. It is about understanding how modern systems—legal, bureaucratic, and ideological—can be weaponized against human beings.

Auschwitz did not operate in secrecy. It functioned through cooperation, silence, and normalization. Ordinary procedures enabled extraordinary crimes.

Studying individual stories helps prevent abstraction. It reminds us that policies affect people, and that indifference has consequences.

The lessons of Auschwitz are not limited to one time or place. They apply wherever identity is reduced to category, and humanity is treated as expendable.

A Name Restored

Aron Löwi did not leave behind diaries or recorded testimony. He did not survive long enough to tell his story. What remains is a photograph, a number, and a handful of verified facts.

That is enough.

History does not require embellishment to be meaningful. Sometimes, accuracy and restraint speak more powerfully than dramatic language.

By remembering Aron Löwi, we acknowledge a life that was taken and a system that failed humanity. We affirm that even the shortest existence within the camp deserves recognition.

They could take his life.

They could assign him a number.

They could limit his existence to five days.

They could not erase his face.

Conclusion: The Responsibility of Memory

Every generation inherits the responsibility to remember—not out of guilt, but out of recognition. Memory is how societies signal what they consider unacceptable, what they refuse to normalize, and what they commit to preventing.

Aron Löwi’s photograph endures because it asks nothing from us except attention.

To look.

To acknowledge.

To remember that behind every number was a person who mattered.

History cannot restore what was lost. But it can ensure that loss is not forgotten.

And sometimes, that is the strongest answer to those who believed erasure was permanent.

Sources

-

Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum – Prisoner card no. 26406

-

Yad Vashem – Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names

-

USC Shoah Foundation – Archival records of early Auschwitz deportations