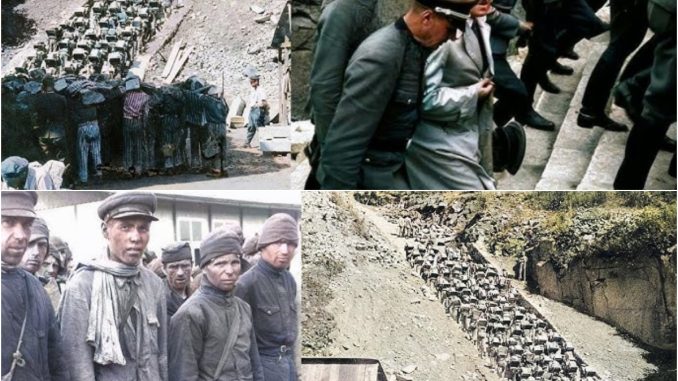

During World War II, the Nazi concentration camp system relied not only on mass shootings and gas chambers but also on methods designed to destroy human beings through exhaustion, deprivation, and systematic abuse. One of the most infamous examples of this approach was found at Mauthausen Concentration Camp, a camp that became a symbol of what the Nazis called “extermination through labor.”

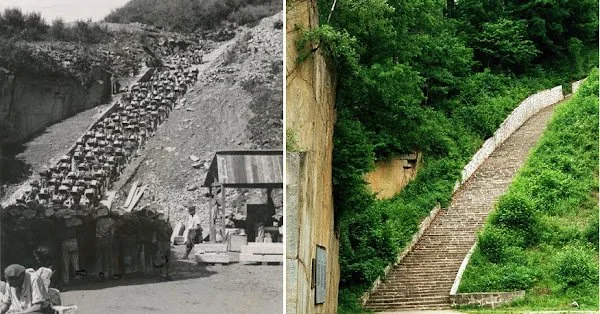

Among the many elements that defined Mauthausen’s brutality, the stone staircase linking the Wiener Graben granite quarry to the camp above has become one of its most enduring symbols. Known today as the “Stairs of Death,” this structure was not a mechanical execution device. Instead, it represented how forced labor itself was turned into a tool of destruction.

Mauthausen and Its Purpose

Mauthausen was established in 1938, shortly after Nazi Germany annexed Austria. Located near the Danube River and close to large granite deposits, the camp was strategically chosen for its economic value. Granite extracted from the nearby quarry was intended for monumental construction projects that symbolized Nazi power.

From the beginning, Mauthausen was classified as a high-severity camp. Prisoners sent there were considered enemies of the regime or individuals deemed expendable. Over time, the camp held political prisoners, prisoners of war, Jews, Spanish Republicans, Roma, and others targeted by Nazi racial and ideological policies.

Unlike some camps primarily designed for detention, Mauthausen combined imprisonment with relentless physical labor under conditions that made survival increasingly unlikely.

The Quarry and the Staircase

The Wiener Graben quarry lay below the main camp, separated by a steep slope. To move quarried stone upward, prisoners were forced to climb a narrow stone staircase consisting of 186 uneven steps. The climb rose several dozen meters from the quarry floor to the camp level.

Prisoners were required to carry heavy stone blocks repeatedly throughout the day. The work was performed while malnourished, poorly clothed, and often wearing unsuitable footwear. The staircase itself was irregular and physically demanding even under normal conditions. Under the circumstances imposed by the SS, it became a site of constant danger.

The stairs were not designed as a formal execution site. However, the conditions under which prisoners were forced to use them made injury, collapse, and death frequent outcomes. The staircase thus became an integral part of a system where labor was deliberately pushed beyond human limits.

“Extermination Through Labor”

Nazi authorities referred to this policy as “annihilation through work.” At Mauthausen, forced labor was structured to extract economic value while simultaneously breaking prisoners physically and mentally.

Prisoners were driven to work at a pace that ignored exhaustion or injury. Falling behind could result in punishment or removal from the labor detail, which often meant death elsewhere in the camp. Survival depended not on completing sentences, but on enduring conditions that were intentionally lethal over time.

The staircase embodied this logic. Each ascent was a test of endurance. Each descent offered no relief, as prisoners were sent back to repeat the process again and again. Weather conditions, including cold and rain, further increased the strain, while medical care was minimal or nonexistent.

Psychological Impact

Beyond physical suffering, the staircase had a profound psychological effect. The repetitive nature of the labor, combined with the visible toll it took on others, reinforced a sense of futility. Prisoners were forced to witness the collapse of fellow inmates while knowing they would soon face the same ordeal.

Survivor testimonies describe the quarry work as one of the most demoralizing experiences of the camp. The staircase was not only something prisoners climbed—it was something they came to fear as a daily confrontation with their own physical limits.

This constant exposure to danger and exhaustion served the SS’s broader goal: to erase individuality, dignity, and hope.

Scale of Suffering

Mauthausen held approximately 200,000 prisoners between 1938 and 1945. Historians estimate that more than half of them died. While deaths occurred in many parts of the camp system, the quarry labor and staircase contributed significantly to this toll.

It is important to note that not every prisoner assigned to the quarry died on the stairs, and deaths were not confined to a single method. Rather, the staircase functioned as part of a larger structure of violence, neglect, and deliberate overwork that ensured high mortality rates.

The cumulative effect of these conditions made survival increasingly unlikely the longer a prisoner remained assigned to quarry labor.

Visibility and Complicity

One of the disturbing aspects of Mauthausen was its visibility. The camp was not hidden deep in remote wilderness. It stood near towns and was visible from surrounding areas. Local industries benefited from the quarry’s output, and the presence of forced labor was widely known.

This proximity highlights an uncomfortable truth: the camp’s operation depended not only on SS guards but also on bureaucratic systems, economic demand, and societal silence. Mauthausen was part of a broader network that normalized exploitation under the guise of wartime necessity.

Liberation and Aftermath

Mauthausen was liberated by U.S. forces in May 1945. What they found shocked even experienced soldiers: thousands of severely weakened prisoners, mass graves, and evidence of systematic abuse.

In the postwar period, Mauthausen became a key site for documenting Nazi crimes. Trials held in connection with the camp helped establish the legal principle that forced labor under lethal conditions constituted a crime against humanity.

Today, the site operates as a memorial and museum. The staircase remains intact, not as a spectacle, but as a place of reflection.

Remembering Without Sensationalism

Modern discussions of the “Stairs of Death” often risk focusing on shock value rather than understanding. While the name itself is stark, its importance lies not in gruesome detail, but in what it represents: how ordinary infrastructure can be transformed into a weapon when human life is stripped of value.

The staircase stands as evidence that genocide does not require complex machinery alone. It can be carried out through everyday processes—work, discipline, routine—when guided by ideology that defines certain people as disposable.

Lessons for the Present

Studying Mauthausen and its forced labor system is not only about the past. It raises questions that remain relevant today:

How do systems normalize cruelty?

How does economic benefit override moral responsibility?

At what point does obedience become complicity?

The Holocaust demonstrates that large-scale atrocities are rarely sudden. They are built step by step through policies, practices, and silence.

A Site of Memory

Today, visitors to Mauthausen walk the same ground prisoners once climbed under unimaginable conditions. The preserved staircase no longer serves its original function. Instead, it serves as a memorial to those who were subjected to forced labor and whose lives were cut short by a system designed to destroy them.

Remembering the “Stairs of Death” means acknowledging that the Holocaust was not only about killing centers, but also about labor camps where death was embedded into daily routine. It is a reminder that dignity, when stripped away systematically, can turn work itself into a means of annihilation.

By studying these sites with care and respect, societies reaffirm a commitment to human rights, historical truth, and the responsibility to prevent such systems from ever being rebuilt.