In 1845, in the state of Mississippi, a case unfolded that was never meant to be spoken of again.

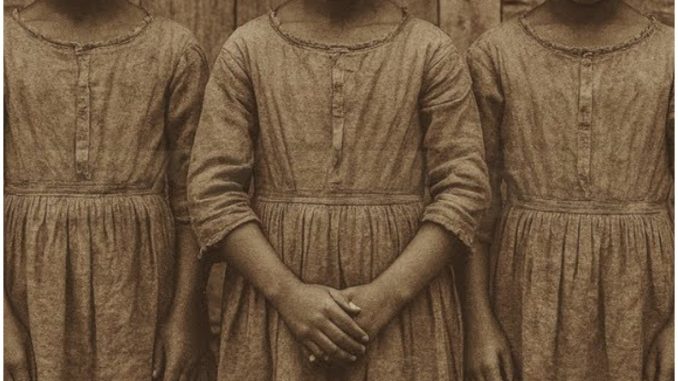

It survived in corners and half-sentences. In the way people lowered their voices when the subject drifted too close. In marks scratched into wood and memories carried like contraband. It was the story of three sisters born together in bondage—three girls who seemed to resist not only the rules of the plantation, but the belief at the heart of it: that a person could be owned, measured, and made small.

They were called triplets, though no public ledger ever honored them with names. People said they moved as one, breathed as one, and carried a humming sound that unsettled anyone who tried to pretend it was nothing. And when they disappeared, their absence landed with such force—so quiet, so complete—that the very men who claimed the land tried to erase the evidence with silence and fire.

But erasure does not always work.

Fragments remain. And inside those fragments sits a truth too heavy to ignore.

The triplets came into the world beneath a night thick with thunder. Their mother—enslaved, exhausted, and given no gentleness—labored in a cramped wooden cabin that smelled of rain-soaked earth and the hard reality of survival. When it was over, three daughters lay wrapped in scraps of cloth, identical faces shining with the sweat and shock of arrival.

In any other life, it might have been called a miracle.

At Hollow Creek Plantation, miracles were treated like trouble.

To some, the birth was a warning. To others, a sign. To the overseers, it was something to fear without admitting they feared it. And to the master of the house, it was an opportunity dressed up as curiosity—rare, profitable, and worth controlling.

To their mother, the girls were everything.

She held them with a trembling urgency, as if she already knew time would be stolen from her. She whispered three names into three tiny ears—names no one in power would ever acknowledge, names that sounded like prayers spoken under breath: Sarah. Cila. Serenity.

She had only moments to give them what she could not give them freely: love, protection, the shape of a hope she was never allowed to say out loud.

Then boots approached. Orders followed. And the girls were taken.

Not to the yard where other children learned the rhythms of work and play. Not to the quarters where a mother’s arms might have protected them, even briefly, from a world built to deny protection. They were carried toward the big house and taken beneath it—down into the cellar where stone stayed damp and shadows did not lift.

People later said the master believed the girls were born for something “more” than labor. He wanted to know why three had come where nature should have given one. He wanted to know what could be learned, what could be claimed, what could be turned into proof of his importance.

And so their lives were reduced to study. Their humanity reduced to notes. Their existence made into a secret kept under lock and key.

But the cellar did not contain them.

In their first nights underground, a sound rose through the floorboards—soft, steady, three voices aligned so closely it felt like one breath stretched into music. It drifted up into rooms where people tried to sleep, into hallways where lantern light dimmed early, into corners where servants paused and pretended they were not listening.

The household found the sound unsettling.

The quarters found it harder to name.

Some said it was comfort. Some said it was a warning. Some said it was a hymn without words, shaped by longing the way rivers are shaped by time.

And as the years passed, the humming did not fade the way the master expected silence to fade.

It grew.

From the very beginning, the Hollow Creek triplets were never spoken of in ordinary tones. Their existence became a whisper that traveled faster than permission. Among the enslaved, their birth was a sign—though the meaning shifted from mouth to mouth. Some believed the girls were a gift sent to remind people they were more than what the plantation called them. Others believed the sisters were marked by something older than any sermon offered at the big house—something that did not bend for anyone.

Their mother did not argue with either view. She did not have the luxury of philosophy.

She simply carried their names like embers and refused to let fear turn her daughters into monsters in her mind.

To the overseers, though, the triplets were an inconvenience dressed up as superstition. They muttered about bad luck and poor harvests. They spoke of “unnatural” things without explaining what they meant, as if the word itself could do the work. That year, people later said the dogs hesitated at the treeline. The fields struggled. The air felt heavier after storms. And because men with power often look for something smaller than themselves to blame, three children became an easy target for their unease.

The master insisted he did not believe in curses.

He believed in ownership.

He believed in the prestige of being the man who held something rare. He believed in physicians’ ink, in measurements, in the idea that if you recorded a thing, you controlled it. He sent for doctors from town—men with leather satchels and clean collars who were used to speaking with certainty.

They arrived with tools and confidence.

They left with quieter eyes.

Because the most troubling thing about the triplets was not their likeness, nor the secrecy around them, but the sound they made together. Their humming rose late at night and slipped through cracks in the floor like breath through teeth. It seemed to travel through wood and soil as if barriers were suggestions rather than walls. And once you heard it, you did not forget it.

Children in the quarters covered their ears. Mothers pulled their babies closer. Men who prided themselves on hardness stared into the dark as if waiting for it to move.

The doctors wrote about symmetry. They wrote about shared behavior. They wrote about “unusual unity” in language that tried to sound scientific while circling the truth they could not explain: the girls moved together as if guided by one thought, and the humming did not behave like something taught.

It behaved like something held.

Beneath the plantation house, the cellar carried its own reputation long before the triplets were brought into it. It was damp, cramped, and perpetually cold. Stone walls “sweated” in the humid months. Lanterns struggled to brighten the corners. Sounds echoed strangely, as if the space multiplied them.

This became the triplets’ world—an underground room meant to hide them from other eyes and keep their story from spreading beyond control.

Their mother begged in whispers.

She offered labor, obedience, anything that might buy her even a few minutes at their side. But her plea collided with the oldest lie of the plantation: that a mother’s love did not matter if it belonged to someone who was not treated as fully human.

So the girls remained below.

Servants carried food down and left it without conversation. A house worker confessed later that when she approached the door, she could feel the sound before she heard it—like a vibration in the air that made her stomach tighten. Sometimes the humming was so low it felt more like pressure than music. Sometimes it rose into a harmony so clean it made people stop mid-step.

Those forced to enter the cellar returned with strange stories. Not sensational ones, not the kind meant to entertain. The kind people tell when they are trying to describe something real and failing. They spoke of the triplets sitting close together, hands linked as if one grip could anchor all three. They spoke of the way the girls’ eyes followed movement without panic—watchful, calm, as if the cellar belonged to them more than it belonged to the master above.

And always, they spoke of the humming.

The master tried to treat it like a nuisance. He ordered it stopped the way he ordered everything else stopped. But the triplets did not answer his authority the way he expected. They did not perform fear on command. They did not give him the satisfaction of pleading.

The sound continued—never loud enough to be called a riot, never aggressive enough to be called an attack, but steady in a way that unsettled the men who believed steadiness belonged only to them.

The physicians attempted explanations that could fit inside a respectable notebook. They wrote about instinct, about mimicry, about siblings influencing each other. Yet their pages began to change. Their handwriting grew more rushed. Their sentences grew shorter. Their words drifted from certainty into unease.

One wrote that the sound “lingered.”

Another wrote that it “followed.”

A third stopped mid-thought, the pen trailing off as if the writer had been interrupted by something he could not name.

Not everyone who heard the humming turned away from it.

In the quarters, children began to whisper about the girls in the cellar the way children whisper about any forbidden story—half terrified, half compelled. They lingered near the heavy door when they could, pretending to fetch water or sweep steps. They pressed their ears to the wood and listened, trying to decide if the humming carried a pattern.

And some swore it did.

A boy no older than ten told his mother he dreamed of the triplets standing at the edge of the fields, hands clasped, pointing toward the treeline. In the dream, he felt a path without seeing it, as if the sound itself mapped the world. He said he always woke before he reached the water.

His mother hushed him quickly.

But stories do not stop because someone says they should.

Soon others said they had dreamed the same. Not with the same details, not like rehearsed lines, but with the same feeling: that the humming carried direction, not just melody. That it did something to the mind. That it planted images of rivers and dark woods and a horizon wider than the plantation.

Adults warned their children to stay away. The plantation punished curiosity. The wrong rumor could draw the wrong attention. And attention in that place could ruin lives.

Still, the humming traveled. The younger ones heard it and wondered. The older ones heard it and felt something heavier—a reminder that even in a world built on control, not everything surrendered.

The master could not tolerate what he could not manage.

He decided the sound had to be broken out of them.

His methods were the same methods used everywhere power insists it is entitled to obedience: deprivation, intimidation, isolation, the idea that comfort can be removed until a person becomes easier to shape.

But the story that survived does not linger on details of cruelty. It lingers on what the master could not understand.

The humming did not disappear.

It softened at times, then returned. It deepened, as though the girls had found something inside themselves that punishment could not reach. Separating them did not silence it, either. The sound came from different corners at once, each voice holding the same note until the room itself felt filled.

Workers later said that some men refused to go down there after a while. Not out of kindness. Out of fear—fear that the cellar was doing something to their thoughts, fear that the sound had a way of slipping past the walls they kept in their minds.

What truly unnerved the master was not noise.

It was refusal.

A refusal that did not shout, did not beg, did not bargain. A refusal that simply existed, steady as breath.

In the summer of 1846, storms began to roll in with a violence that people remembered for years. Clouds arrived dark and sudden. Thunder cracked so sharply it made the house tremble. The plantation had seen storms before, but those felt different—closer, louder, almost personal.

During the worst of them, the triplets’ humming rose higher than anyone had heard it. Servants claimed the lanterns in the hallway flickered in rhythm with the sound. Men posted near the cellar said their hearts seemed to speed up and stumble as if trying to match a tempo they could not control.

One guard later swore he saw three small figures standing where no window existed, briefly lit by lightning.

Another said he felt the stone steps vibrate beneath his boots.

Whether these were true sightings or fear playing with the mind, no one could prove. Proof was not the point.

The point was that the plantation no longer felt stable.

And when a place built on domination begins to feel unstable, the people who benefit from it panic.

All the while, their mother carried the quietest suffering of all.

She lived close enough to the cellar to imagine every breath her daughters took and far enough to do nothing but imagine. She found small ways to reach them—lingering by the door when she was sent to the kitchen, pressing her palm to the wood as if touch could become comfort. On rare cleaning days, she left crumbs of bread, a scrap of cloth, a whispered prayer in the air like a thread thrown into darkness.

The triplets never answered with words.

But sometimes, when her hand rested against the door, the humming shifted—deepening for a moment, as if acknowledging her presence.

She spoke little of them in public. Naming them aloud was dangerous. But in her own breath, late at night when the quarters went still, she repeated the three names like a vow: Sarah. Cila. Serenity.

Grief made her smaller. But it did not erase her.

If anything, it made her more watchful, as if she were waiting for a moment the plantation could not predict.

By 1847, the humming was no longer treated as a strange habit.

It was treated as a force.

It moved through the plantation like weather. It shaped nights. It rearranged moods. It made men drink more, speak less, and glance over their shoulders as if they feared being followed by something they could not see.

The physicians returned, but their confidence did not.

Their notes became fragmented. Their pages filled with words that looked like they were written by hands that could not stay steady. Measurements appeared beside half-finished sentences. Diagrams sat next to lines that did not belong in a scientific ledger.

One entry ended after: “The girls do not—”

Another read: “The sound does not cease. It follows.”

A final fragment surfaced years later, allegedly found folded into an old medical book far from the plantation. Its edges were singed, as if it had survived a fire by accident or by intention. The handwriting was shaky, the ink blurred, but the meaning still pressed through:

The subjects persist beyond expectation. Their voices do not fade with time or distance. The sound alters the air. I fear it alters me. This is not a matter of science. This is something else.

Then, one last line, underlined twice:

They do not die.

People argued about what it meant. Some dismissed it as a man unraveling under guilt or superstition. Others treated it as evidence that the triplets were never as contained as the master believed.

Not long after, the doctors stopped coming.

The ledgers stopped, too—pages growing sparse, weeks left blank as if the act of recording had become a kind of risk.

Then came the overseer.

Every plantation had a man whose name was spoken carefully, the one trusted to enforce order when others hesitated. At Hollow Creek, that man was Harlon Price. He was known not for mercy, but for pride in obedience. He volunteered to go down to the cellar when others avoided it. He went with a lantern and the certainty that fear was something you could manufacture in a child.

Witnesses later said the humming stopped the moment he entered, as if the girls had been waiting.

Silence filled the cellar so thick it felt like pressure.

Then the humming returned—not soothing, not low, but sharp in its precision. Three tones braided together so cleanly it startled the men who listened at the stairwell.

Harlon’s voice rose in threats.

And then, abruptly, his voice faltered.

The lantern light shook. The sound grew steadier, as if it had found a rhythm and refused to lose it. Moments later, Harlon came back up the stairs with a face drained of confidence. He did not speak. He did not laugh. He did not look anyone in the eye.

That night he was seen sitting outside in the dirt, rocking slightly, his hands trembling as if they no longer trusted his own strength.

Within days, Harlon vanished.

No one could agree on how. Some said he ran into the woods. Some insisted he was “taken” by whatever lived beneath the house. No grave was dug. No certainty offered.

But after he disappeared, the other men kept their distance from the cellar.

And the plantation changed.

The big house grew quieter. The overseers’ swagger thinned. Work continued, because work always continued, but the air felt different—like everyone was waiting for something to break.

In the quarters, the humming shifted again. It grew lower, longer, less like a melody and more like a deep drone that lived under the skin. Children complained of uneasy sleep. Adults spoke of feeling watched, though no eyes were upon them. People began to treat the sound like a prayer, or like a warning, depending on what they needed to believe in order to survive another day.

Then, in the summer of 1848, the fragile balance shattered.

It began as a whisper passed from child to child. People said the humming no longer belonged only to the cellar. It reached farther now, weaving itself through night air, curling into the quarters like smoke. One evening, when the moon hung low and pale, families gathered without anyone calling them. Drawn as if by a shared instinct, they stood at the edge of the fields where tilled earth met the dark line of the woods.

No one spoke.

They listened.

And from beneath the master’s house, the sound rose.

It was not gentle this time. It was layered, almost choral, as though more than three voices had joined in. The tones wrapped around each other and pressed outward until the air felt thick with it.

Some fell to their knees, tears slipping down their faces. Others clasped hands, stunned by a feeling they could not name—something close to hope, but sharper, more dangerous.

When the sound faded, the crowd lingered, unwilling to break whatever spell had drawn them together. They returned to their cabins carrying not answers, but a sense that they had been summoned.

And soon, the plantation discovered what the summoning meant.

The next morning, servants carried the usual bowls down to the cellar. At the bottom of the stairs, they paused. The air felt wrong—too still, too heavy, as if the cellar had emptied itself and left the space hollow.

When the door opened, the room lay in silence.

The straw beds were undisturbed. The bowls sat as they had been left. The chains fixed to the walls hung empty, iron cuffs swinging gently as if stirred by an unseen breath.

And the triplets were gone.

Panic raced through the house. The master stormed down himself, shouting demands into a room that offered no reply. Overseers searched for broken locks, hidden tunnels, tracks in the dirt.

There were none.

No door stood open. No lock had been forced. No obvious path led out.

The girls had been there one night.

By dawn, they were simply gone.

The master reacted the way men like him always react when control slips: he accused others. He threatened. He demanded confessions. He punished people for not knowing what he refused to understand.

But no one could explain it.

And then, as if the plantation itself had been holding its breath, the fire came.

It started in the lower part of the house—exactly where, no one could agree. Some said it began near the cellar. Others insisted it began where papers were stored, where records were kept. The flames moved fast, swallowing wood that had stood for decades.

Servants hauled water. Men shouted orders. But the blaze resisted panic and discipline alike. It spread as if it had chosen its own path.

Those who watched later said something that made the story endure: they heard the humming again, woven through the crackle of the fire. Not loud. Not triumphant. Simply present, steady in the smoke as if the sound had stepped out of the cellar and into the night.

By sunrise, part of the house was ruined.

No bodies were found in the ashes. No trace of the triplets appeared.

Only scorched beams, blackened stone, and a silence heavier than anything the plantation had ever tried to enforce.

After that, the master did what power always does when it is frightened.

He turned to ink.

Ledgers were cleaned. Entries were altered. The mother’s record was rewritten to suggest a single child, not three. The physicians’ journals vanished. If they existed at all, they were burned or hidden or carried away by hands no one admitted seeing.

To outsiders, the master claimed it was a simple accident—a kitchen flare, an unfortunate mishap, a story meant to end questions quickly.

Inside Hollow Creek, no one believed him.

Among the enslaved, the memory did not vanish with the paper.

Mothers whispered the girls’ names into the dark. Fathers carved three small marks into cabin walls. Children hummed softly when they thought no one was listening, as if the tune had lodged itself in their bones.

Because ink can be erased.

But memory breathes.

It hums.

It waits.

As years passed, the story traveled beyond Hollow Creek. People sold to other places carried the melody with them, folding it into work songs, into spirituals, into lullabies sung to restless children. The tune changed as it moved, blending into larger choruses, but at its heart remained the same three tones—linked like clasped hands.

Long after slavery ended and the old plantation fell into ruin, people still avoided the land. Travelers spoke of uneasy nights. New families who tried to live nearby complained of faint humming rising through the floor on stormy evenings. Some dismissed it as imagination, the mind filling silence with story.

Others left.

Among descendants of those who had been enslaved there, the triplets became something else entirely—not ghosts to fear, but voices to remember. A reminder that even children had refused to become only what the plantation wanted them to be.

And the riddle remained.

Were they three girls who escaped through help no one dared record? Were they lost to the river or the woods, their fate swallowed by a world that did not preserve the vulnerable? Or did their story transform into legend because legend was the only way to carry something too painful for records?

No grave was found. No official ending uncovered.

And perhaps that is why the story endures: because unfinished stories do not stay quiet. They return. They ask to be told again, not to entertain, but to insist that something happened here that power could not fully erase.

The masters tried to bury the triplets twice—first in chains, then in silence.

Neither burial held.

Their names were never printed in neat columns. Their fate was never settled on paper. But their humming outlived the men who tried to claim them. It traveled through storms, through years, through the brittle gaps of history where so many lives disappeared without ceremony.

The case of the Hollow Creek triplets remains unsolved.

Not because no one looked.

But because the world that created Hollow Creek was designed to lose people on purpose—and then call the loss normal.

Yet here we are, still hearing the story.

Still repeating it.

Still feeling that strange, steady thread running beneath it, like a low note held in the chest.

The case is not closed.

Perhaps it never can be.

And on the stillest nights—when thunder sits far off, when the air turns heavy, when the world pauses long enough for you to notice the quiet—some say you can almost imagine it: three voices, aligned as one breath, humming from a place no ledger can reach.