In 79 AD, beneath the stone floors of Rome’s newest and loudest arena, a nineteen-year-old woman named Sabina stood in darkness.

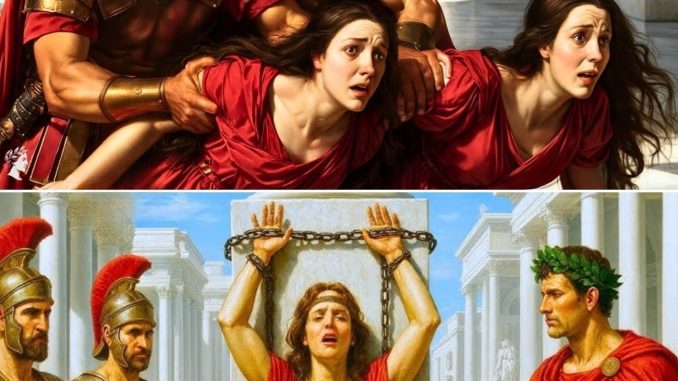

Above her, more than fifty thousand spectators filled the seats of the Colosseum, roaring in approval as a gladiator delivered the final blow to the last of her brothers. The sound of the crowd did not reach her as noise. It reached her as vibration—through stone, through chains, through bone.

What followed over the next several hours was not recorded in marble inscriptions or victory poems. It was discussed only in whispers, erased from official histories, and later debated by Roman scholars who disagreed on whether it should ever be written down at all.

Not because it did not happen.

But because admitting it would have forced Rome to confront what its entertainment truly cost.

This is the story Roman senators tried to bury. Not a tale of random cruelty, but of a reward system—one so normalized that it became invisible to those who benefited from it. A practice that turned victory into entitlement and human beings into inventory, behind locked gates and beneath cheering crowds.

The Colosseum was not merely a structure. Completed only a year earlier, it was Rome’s most refined instrument of dominance. Its sand-covered floor existed to absorb the visible consequences of violence. But below that sand lay something far more deliberate: a network of chambers, corridors, and holding cells designed to process the defeated.

The condemned.

The captured.

The conquered.

Gladiatorial games were never only sport. They were political messaging, ritualized punishment, and social intimidation combined into spectacle. When Roman forces crushed the Deon uprising in 78 AD, the victory parade did not end with weapons and treasure. It included hundreds of captives—among them women of rank, lineage, and symbolic importance to their people.

Rome understood something fundamental about power: defeating an enemy’s army was not enough. To prevent future resistance, their identity had to be broken.

That afternoon, Sabina stood among other captives in a subterranean holding cell. Her village no longer existed. Her future had already been decided by men who would never learn her language or her name. She did not yet understand what it meant when a guard told her she had been “selected.”

She would soon learn that Rome’s idea of mercy could be more devastating than open brutality.

This was not chaos. It was policy.

The Roman system categorized people with ruthless efficiency. Victors received formal rewards—money, honors, status. But alongside these tangible prizes existed something far darker: private privileges granted beyond public view. These practices were rarely written about directly, yet referenced obliquely by Roman writers who clearly expected their audience to understand what was left unsaid.

As the afternoon progressed, arena officials prepared what they called an interlude—secondary entertainment staged between major combat events. Historically, these interludes often involved forced reenactments, symbolic punishments, or ritualized humiliation of the defeated.

That day, the spectacle was designed not to kill immediately, but to degrade publicly.

Captured women were brought into the arena under the pretense of mock combat. Wooden weapons were distributed. The outcome was predetermined. Resistance was expected to entertain the crowd. Compliance was demanded.

When Sabina and another woman refused to perform, the illusion collapsed. Guards intervened. The audience reacted with confusion, then anger. What followed was not improvisation. It was procedure.

Records recovered centuries later describe administrative notes written with chilling neutrality. Captives processed. Resistance logged. Individuals reassigned.

Human lives reduced to line items.

Below the arena, chambers waited—clean, organized, unmistakably intentional. These rooms were not makeshift. Archaeological evidence confirms they were part of the original construction. Stone benches. Iron restraints embedded in walls. Doors designed to lock only from the outside.

This was infrastructure.

It is here that one small fracture appeared in Rome’s machinery.

The victorious gladiator that day, Gas Valerius Maximus, entered one of these chambers. By Roman law, he held absolute authority over the captive assigned to him. The system required nothing further from him. Compliance was assumed.

Instead, something unexpected occurred.

According to later clerical records, no violence was reported. Guards noted voices, conversation, then silence. Time passed. When the gladiator emerged, he invoked a rarely used procedural exemption, declaring the captive unfit for allocation.

The claim was bureaucratic. The reason was never investigated.

Sabina was transferred away from immediate harm—but not to safety. Overcrowded medical holding areas beneath the arena were notorious for neglect. She died days later from infection, a fate so common it barely warranted notation.

Her survival from one form of destruction led directly into another.

The gladiator’s refusal did not go unnoticed.

In the weeks that followed, whispers circulated among trainers and fighters. A man had declined his entitlement. Others began to question what was expected of them. One junior gladiator was punished for following that example.

That punishment reached the Senate.

Not because of moral outrage—but because discipline within Rome’s most visible institution was at risk. Senate records from late 79 AD reference a debate about “customs concerning defeated female captives,” phrased so mildly it barely conceals the intensity of the argument behind it.

Traditionalists defended precedent. Reformers warned of consequences. Provincial governors reported that stories of these practices were spreading beyond Rome, fueling rebellion rather than suppressing it.

The result was a limited but unprecedented law.

Female captives could no longer be distributed as public rewards in arena contexts. Public humiliation in spectacles was restricted. Enforcement was inconsistent, and private exploitation continued—but something had shifted.

Not because Rome had found compassion.

Because Rome had found inconvenience.

Months later, Gas Valerius Maximus earned his freedom through additional victories. His final recorded act as a free man was the purchase of a captive woman’s release—one historians believe may have been the same woman who stood beside Sabina that afternoon.

Nothing more is known of her.

Sabina’s name survives only because a single bronze tag bearing the word captiva was recovered during excavations in 2018 by archaeologists working in the eastern hypogeum. The chambers they uncovered were never meant to be seen. Drainage channels. Restraints. Scratches carved into stone by hands that left no other record.

Carbon dating confirmed these rooms were part of the original design.

Roman historians were not ignorant of these practices. Cassius Dio referenced allocation customs indirectly. Seneca hinted without detail. Tacitus, normally explicit, was conspicuously silent.

Silence, in this case, was not absence of knowledge.

It was choice.

Rome’s tragedy was not cruelty alone. Ancient warfare was brutal everywhere. Rome’s distinction was standardization. It transformed suffering into routine, humiliation into policy, and entertainment into moral anesthesia.

The empire built aqueducts that still stand today—and chambers beneath its arenas where people vanished without record. Its genius and its emptiness existed side by side.

This story matters not because it shocks, but because it explains how civilizations justify harm through tradition, paperwork, and applause. How power turns victims into abstractions. How systems corrupt even those trapped inside them.

Sabina did not survive long enough to be remembered.

But the stone beneath the arena did.

And it still asks the same question of every generation that walks above it:

What are we willing to excuse, as long as we don’t have to watch?