In the spring of 1200 BC, a young girl named Nefertari stood in the open courtyard of the temple of Amun at Karnak as temple attendants shaved her head down to bare skin. She was nine years old. Three days earlier, her father—a low-ranking official—had brought her there because he owed the temple a debt he could not repay with silver or grain.

So he repaid it with his child.

Nefertari didn’t understand the exchange she had been placed inside. She only knew what she had been told: that this was an honor, that she would serve the gods, that she should be thankful, quiet, and obedient. As the bronze blade passed again and again over her scalp, taking away the long black hair she used to wear in careful braids, she began to cry.

An older temple woman struck her hard and spoke without warmth. “Those who serve the god do not weep,” she said. “You don’t have tears anymore. You don’t have a name anymore. You belong to Amun now, and Amun does not welcome weakness.”

That was Nefertari’s first day in a life that would last more than four decades. A life defined by isolation, control, and a system of exploitation that could hide behind painted walls and sacred imagery.

She would not leave the temple grounds. She would not marry. She would not own anything in her own right. She would not make meaningful choices about her body, her time, or her future. She would serve until she died, then disappear into a burial with no marker and no family allowed to grieve her as a daughter with a story. And most people never hear about this part.

Because Nefertari was not rare.

She was not a single “bad exception” in an otherwise noble institution. She was one of many girls and women who lived and died inside temple complexes across ancient Egypt—known by titles that sounded beautiful, holy, even elevated, while masking what their lives often contained.

They were called “wives of the god,” “servants of the god,” “hands of the goddess,” “pure ones,” “divine adorers.” Words designed to inspire awe. Words that could also function like a curtain.

Behind that curtain was a system that could absorb vulnerable people with the same efficiency as any large institution: taking children, reshaping identities, enforcing obedience, and normalizing control so completely that outsiders would see devotion where insiders lived captivity.

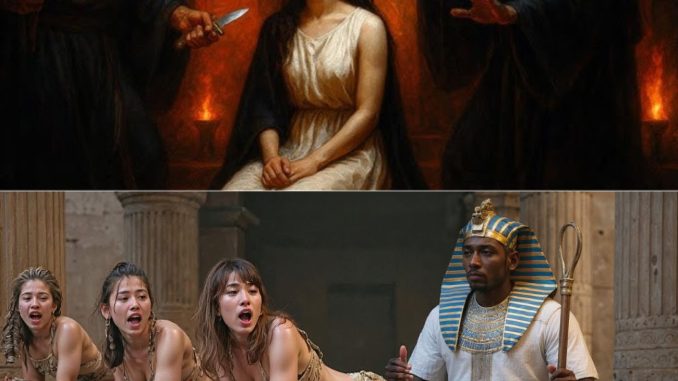

This is a story about what happened to girls dedicated to temple life. And before you go further, you should understand something important: modern romantic images of “temple virgins” can be wildly misleading.

When many people picture priestesses in ancient Egypt, they imagine dignified women in white linen, honored spiritual servants, living a chosen life of ritual and meaning. They imagine protection, prestige, purpose—something like a sacred calling.

That picture is incomplete, and in some cases it’s deeply wrong.

Part of the reason it survives is that the language of power is often beautiful. Institutions don’t describe themselves the way the powerless would. They describe themselves the way they want to be remembered.

So let’s begin with what these roles actually were.

In Egyptian religious life, women in temples could hold a range of positions and titles. Some terms often translated as “servant of the god” or “wife of the god” appear in inscriptions and records. Other titles describe worshippers, singers, musicians, and attendants. The hierarchy could be complex, and responsibilities varied by temple and era, but many of these roles shared a core reality: the women were bound to the temple, controlled by its authority, and expected to live by rules that could erase autonomy—and sometimes identity.

The modern word “virgin,” when applied here, needs extra care. In ancient religious contexts, “purity” often referred to ritual status—being separated from what was considered ordinary or profane. But ritual purity could be enforced through intense supervision and rigid control of personal life, including relationships. “Purity” was not simply an internal spiritual state. It could become an external regime.

And here is the crucial point.

Many of these girls did not choose this path.

Some were dedicated by families as offerings—framed as devotion, a vow fulfilled, a request for divine favor, or simply a way to reduce hardship at home. The story would be told as sacred giving. For the child, it could mean permanent separation: a clean break from family ties that would never fully heal.

Others were handed over as repayment for debt—exactly like Nefertari. Temples were not only religious centers. They were economic powers: landholders, lenders, tax collectors, storage hubs. In a world where temples managed grain, labor, and wealth, a family trapped by obligation could be pushed into “payment” that was really the transfer of a human life into institutional control.

And there were also girls taken as part of conquest and tribute. Egyptian campaigns and expansions brought captives from Nubia, Libya, and regions of the Levant. Among the spoils of power were people—children included—absorbed into Egyptian systems as labor and service. Some were assigned to temples and never returned home.

What shocks modern readers most is the age at which this could begin.

Some records and inscriptions suggest girls entered temple service at eight or nine—sometimes even younger, though ancient documentation doesn’t always preserve exact ages the way modern systems do. What is clear is that many were children, not capable of understanding what “dedication” truly meant, not able to consent to the life that would shape every year ahead.

Consider another child: Mutmua.

She was eight when soldiers came to her Nubian village after Egypt asserted control over the region during the reign of Thutmose III. The soldiers collected tribute—gold, ivory, grain—and children. Mutmua was selected with a group of girls from different families. They were bound together and marched north for weeks.

She did not speak Egyptian. She could not understand the commands shouted at her. She only knew that she had been taken from her mother, from her siblings, from the only life she recognized. She cried until she learned crying brought consequences. So she learned to make no sound even as tears fell.

When the group reached Egypt, the girls were divided among temples. Mutmua was assigned to the temple of Mut, a goddess associated with queenship and motherhood—an association that would become bitter over time as Mutmua slowly realized she was serving an ideal of motherhood while being denied an ordinary family life of her own.

Now pay attention, because what happened next is the part that turned children with names and histories into “temple property.”

When a girl was designated for temple service—through vow, debt, or conquest—she often went through rituals that dismantled her old identity and rebuilt her as someone who belonged to the institution. These processes could stretch across days or weeks. They weren’t only religious acts. They were also social engineering.

The first step was often purification through washing. On the surface, it sounds harmless: cleansing with water, natron, and ritual words. But in a controlled system, even “purification” can become a tool. The child would be stripped of her old clothing and personal markers. She would be examined, instructed, corrected, and taught immediately that her discomfort did not matter.

Nefertari’s purification was held in a stone pool inside a closed courtyard. Priests and senior temple women supervised. She was told to undress. When she hesitated—afraid and embarrassed—her clothing was taken from her. The water was cold. She tried to cover herself. She was ordered to stand still, to obey, to submit to inspection in the name of “worthiness.”

What matters here is not a sensational description. What matters is the pattern: a child learns, on day one, that authority can access her body, regulate her emotions, and redefine boundaries—while insisting it is sacred.

After purification came the shaving of the head, as in Nefertari’s opening scene. It was justified as purity and uniformity. In practice, it also served a psychological purpose. Hair—especially for a child—can be identity, pride, familiarity. Removing it makes a person look and feel like someone else. It announces, to the child and to everyone who sees her, that the previous life is over.

Then came renaming.

A birth name connects a child to family, memory, and origin. A new name connects her to the institution. Sometimes the new name referenced a deity: “Beloved of Amun,” “Beautiful for Hathor,” “She who belongs to Mut.” Sometimes it reduced a person to function: “She who sings,” “She who serves.”

Nefertari, we are told, was renamed with a temple-approved name. Her old name became forbidden—something she was not allowed to speak, and eventually not allowed to think of as “hers.” The message was clear: the daughter of a family had been replaced by a role within a system.

And after this came something described in sources and later retellings as a “divine marriage.”

In some traditions, girls assigned to certain temple categories underwent ceremonies symbolically binding them to a god. They were dressed in special garments, led into restricted spaces, made to recite vows of lifelong service, and publicly positioned as belonging to the deity.

Mutmua’s ceremony at the temple of Mut happened when she was about ten. She had been in the temple long enough to speak Egyptian and follow instructions without hesitation. She was dressed in fine linen, adorned with jewelry, and led into an inner sanctuary she had never entered before. Priests chanted. Lamps flickered. The statue of the goddess loomed over the room, its inlaid eyes catching the light.

The high priest spoke as if he were speaking for the goddess herself. Mutmua was told to repeat vows: that her life belonged to Mut, that her body and labor were devoted to the deity, that she had no other loyalty, no other family, no other future.

She repeated the words because she had no choice.

And those vows were not merely symbolic within the society around them. A girl bound this way could be blocked from ordinary marriage. She could be denied property rights. She could be trapped inside temple structures. The “marriage” functioned as a legal and social lock.

Now, daily life.

Inside the temple, the routine was designed to shape the mind as much as the body. For women like Nefertari, life meant waking before dawn in communal quarters under watch. Privacy was scarce by design. Possessions were minimal. Anything from the girl’s former life was removed early. Ownership—over objects, over time, over choices—was not the point of the system.

Morning purification came again: water, natron, plain linen garments. Then labor.

Most women performed long hours of repetitive work that sustained the temple economy: weaving linen for ritual use and trade, preparing offerings of food and drink, grinding grain, brewing beer, tending gardens, cleaning sacred spaces. The work was framed as devotion. But it also produced wealth and stability for the institution that controlled them.

Some women held more visible ritual roles—especially singers and musicians who practiced hymns, learned instruments, and performed during ceremonies believed to please the gods. The songs were sacred. The discipline was strict.

And over all of it was enforced silence.

Speech outside permitted moments was punished. Silence prevented relationships from forming into alliances. It made each woman feel alone even among others. It kept attention focused upward—toward overseers, toward rules, toward fear.

Nefertari’s closest friend, a girl named Takayat, worked beside her at the looms. They weren’t supposed to talk, but sometimes they whispered when the overseer was far away—tiny sentences, almost breathless.

“I dreamed of my mother.”

“Do you remember fruit?”

“How many years until we’re gone?”

One day the overseer noticed. The punishment was immediate and public, meant to teach everyone at once. Takayat was dragged away. When she returned days later, something in her had changed. She no longer whispered. She no longer looked anyone in the eye. Soon after, she disappeared again, and the temple announced she had “failed” and had been “returned to the gods.”

No explanation. No details. Just a warning dressed as religious language.

The surveillance extended far beyond labor.

Women were watched by senior temple women and by priests overseeing operations. Movement was restricted. Leaving the temple required permission and escort. Visitors were forbidden or tightly controlled. Contact with birth families, if it happened at all, could be limited and supervised.

There were also regular “inspections” to ensure ritual purity—another mechanism that reinforced the idea that the institution had the right to scrutinize the most personal aspects of a person’s life. Even when framed as religious procedure, the effect was the same: control, intimidation, and the constant reminder that the woman’s body and choices were not fully her own.

If a woman appeared unhappy, distracted, resistant, or emotionally unstable, she could be reported and punished. Punishments could include harsher labor, reduced food, beatings administered by senior women, or isolation in dark storage rooms for days. The point was not simply discipline. The point was to break hope.

Escape was nearly impossible for another reason: many girls entered temple life so young that they had little memory of the outside world. They had no money, no property, no independent network, no safe place to go. Family ties were deliberately cut. Even if the gates opened, the world beyond could feel like an unknown wilderness.

Walls did not need to be high when the mind had been trained to believe there was nowhere else to live.

And this is where indoctrination came in.

Temples didn’t only want workers. They wanted believers.

From childhood, girls were taught that they were chosen and blessed. That the priests who commanded them carried divine authority. That disobedience was not merely rule-breaking but spiritual danger—punishable in life and afterlife. They were told the outside world was corrupt, spiritually inferior, unsafe. They were told true purity existed only inside the system that controlled them.

This kind of teaching does something powerful: it makes captivity feel like salvation.

But not everyone fully surrendered to it.

When Mutmua was sixteen, she had been in the temple for eight years. She knew the hymns, the language, the routine. But she still remembered her mother’s voice and the songs of Nubia. One night, in the darkness of the sleeping quarters, she quietly sang a Nubian song—words she had not spoken aloud in years.

An older woman heard. The overseer was told.

The next morning, Mutmua was dragged before the high priest and ordered to explain herself. She tried to say it was only a childhood memory, not disrespect. The response was brutal. She was told she had no mother, no language, no songs except those the temple allowed. She was confined for days with little food and water. When she returned, she never sang Nubian words again.

But the memory did not die. It just became a secret grief she carried in silence.

Now, there is a section of this story that many modern retellings push into explicit territory. I’m not going to do that. What matters, and what can be said plainly without graphic detail, is this:

In some temple settings, power imbalances allowed religious language to be used as justification for coercion and exploitation. When an institution controls where you live, what you eat, whether you can leave, who you can speak to, and what happens if you refuse, “consent” cannot exist in any meaningful sense. When religious authority is used to pressure compliance, the harm becomes both personal and structural.

Nefertari, still very young, was at one point “selected” for a ceremony framed as a special honor. She was treated differently, given better food, prepared with extra care, dressed in fine garments. Others looked at her with a mixture of fear and pity.

And then she learned what that “honor” truly meant in practice: not choice, not dignity, not protection—just another way the system could take from her while demanding she call it sacred.

Afterward, she returned to her routine with new knowledge that never leaves a person: that what happened once could happen again, and there was no court to appeal to, no outside authority to tell, no safe exit.

Some women became pregnant within temple life. Children born inside the system could be absorbed into it—raised as temple dependents, trained for service, separated from mothers in ways that reinforced the institution’s ownership over the next generation.

When Nefertari realized she was pregnant as a teenager, she was moved into quarters for pregnant women. For the first time in years, she could speak more openly with others who understood her fear. She was told what to expect: that the child would not fully “belong” to her, that the institution would decide the child’s future, that motherhood inside the system was not the same as motherhood outside it.

She gave birth to a daughter and, for a time, was allowed to care for her. Later, the child was taken for training. Nefertari could see her sometimes in corridors—but was not allowed to claim her, comfort her, or name their bond.

Many who have lived under controlling systems will tell you: one of the deepest wounds is not only what is done to you, but what you are forced to watch happen to someone you love.

Resistance, when it appeared, was dangerous.

Some punishments were framed as “correction” or “cleansing”—fasting, extra labor, isolation, beatings. For the most serious “offenses”—attempting escape, speaking openly against authority, refusing assigned roles—stories describe a final punishment presented as exile: being taken beyond the temple and abandoned in the desert.

The desert, in Egyptian symbolism, was chaos and danger—outside the cultivated world. Abandonment was described as religious judgment. In reality, it was a method of terror meant to warn everyone who remained.

One woman, remembered as Hutmahite in this telling, reached a breaking point and spoke aloud during a meal: that the system was not holy, that they were prisoners, that they should resist. The room went silent. She was seized quickly. The others did not move—not because they did not feel it, but because fear had been engineered into their bones.

She was taken away. The temple made others witness the consequences. The lesson was meant to crush hope.

But another lesson formed quietly underneath: that the system was not divine, and that those who dared to name the truth—at terrible cost—were not “impure,” but brave.

So resistance became small, coded, nearly invisible.

In the way women exchanged glances when priests spoke.

In tiny mistakes made deliberately.

In patterns woven into cloth that carried hidden messages.

In private memories guarded like contraband.

And in a few cases, in secret inscriptions.

Most temple women died inside the precincts after a lifetime of service. Their deaths did not restore their individuality. They were buried as temple personnel, not as daughters, sisters, mothers with a lineage. Burials could be communal, minimal, unmarked. Names were not always preserved. Mourning could be restricted. The system preferred that individuals vanish without echo.

When Nefertari died around age fifty-two after more than forty years in temple life, she was placed in a shared pit with other women who died near the same time. No marker. Little ceremony. Her daughter, now grown, was not allowed open grief. Within days, others were instructed not to speak of Nefertari as a person—only as a role that had ended.

This wasn’t accident. It was design.

But in hidden corners—storage rooms, shadowed passages, places overseers rarely checked—some women carved messages into stone. Small, rushed, easy to miss. Not official inscriptions, not polished declarations. Just scratches made by someone who refused to be erased without protest.

One message, in this retelling, says something like: “I was born free. They took that. Remember we were people. I had another name before they changed it. I loved my children even when I was not allowed to claim them. We did not choose this.”

Mutmua, near the end of her life, is said to have carved her own final note with a stolen bronze tool while counting grain jars in a dark corner. She wrote of her mother’s name, her forgotten language, her refusal to let her inner self be fully taken—even when everything else had been controlled.

Then she died days later.

Her message remained, hidden in the wall, unknown to the priests who buried her without ceremony. Unknown to a daughter taken too young to remember her. Unknown to generations who walked past that room without seeing the faint scratches in stone.

But the words stayed.

A whisper in the dark that outlasted the people who tried to silence it.

This is what the grand temples do not easily show the tourists who admire columns and reliefs. Guides describe pharaohs, gods, victories, and glorious architecture. Far fewer tell the story of the girls and women whose lives were absorbed into those complexes—whose identities were stripped, whose freedom was restricted, whose suffering was often renamed as devotion.

The temples still stand.

Visitors still photograph them.

And the walls still glow with the language of power.

But if you look at those stones differently—if you remember that institutions are built not only from blocks of sandstone but from human lives—you begin to see another history running beneath the official one.

A history of Nefertari, taken at nine.

Of Mutmua, taken at eight.

Of Takayat, broken for a whisper.

Of Hutmahite, punished for speaking.

And of thousands more whose names were never recorded in ways the world would easily find.

They were people.

They endured.

They left traces where they could.

And they deserve to be remembered as human beings—not as decorative titles inside a sacred story, but as lives lived under control, and as voices that tried, however quietly, to say: I was here.