A Widow’s Purchase, a Community’s Whisper, and the System That Made “Love” Impossible

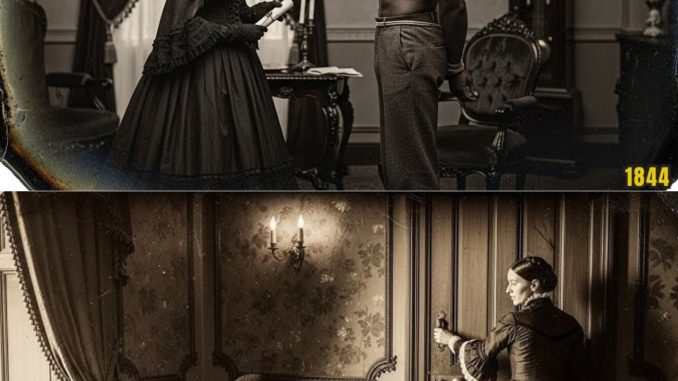

Charleston, South Carolina, 1844. In the heat of midsummer, public auctions drew crowds who treated human lives like inventory. Notices described age, strength, and “productivity” in the same tone used for livestock. It was normal to them, which is part of what made it so devastating.

A story circulated in Charleston society about a young widow who arrived alone at an auction and paid an extraordinary price for an enslaved man being marketed for forced reproduction. The gossip spread quickly because it violated multiple social rules at once: respectable white women were not expected to attend auctions, a widow was supposed to present quiet grief, and the purchase itself hinted at motives people were eager to judge.

Whether every detail of the tale can be verified today is difficult. But the dynamics inside it—the legal power imbalance, the way “ownership” shaped every relationship, and the way society policed women’s reputation while excusing cruelty—match what historians have documented about slavery in the antebellum South.

This is a rewritten, policy-safe version of that narrative, told as a cautionary historical account rather than a sensational “twist” story.

The Auction World That Turned People Into “Assets”

Slave auctions were not just marketplaces. They were public theaters of power. Enslaved people were displayed, inspected, and described using cold language that reduced a person’s body, skills, and future children to numbers on a ledger.

In that environment, an enslaved man could be advertised not only for labor but for “breeding”—a term that treated forced parenthood as a financial strategy. This was not romance. It was an economy that extracted value from every stage of a human life.

For buyers, the math was straightforward: if an enslaved person could be forced to produce children, the plantation’s “property” could grow without new purchases. For the enslaved, it meant that even family formation—normally the most personal part of life—could be manipulated, separated, and commodified.

A Widow Arrives Without an Escort

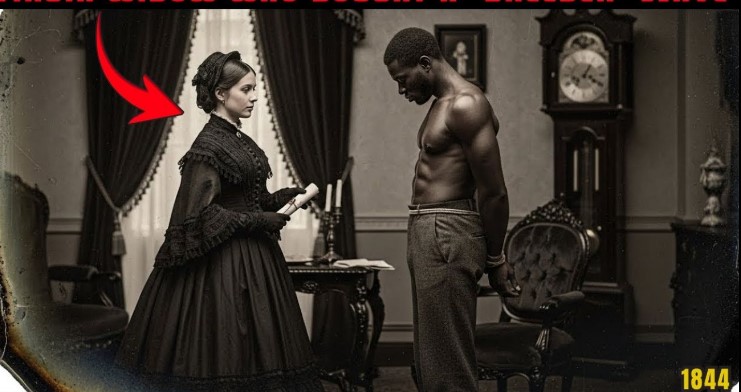

In the story, a widow enters the auction space dressed in mourning, face partially hidden by a veil. People notice her not because she is the only woman present, but because she is alone. In that time and place, a white woman of social standing was expected to be accompanied by a male relative or representative, especially in settings considered crude or “unseemly.”

The moment she bids—far above the highest offer—attention hardens into judgment. Men who had been competing for profit suddenly become spectators of scandal. They assume the purchase must be driven by desire, loneliness, or something they can turn into gossip.

That assumption is revealing. A society comfortable with buying human beings still found it more shocking for a widow to break etiquette than for an auctioneer to describe a person’s body as inventory. The moral compass wasn’t just broken. It was pointed in the wrong direction.

Inheritance, Loneliness, and the Trap of “Respectability”

The widow in the narrative—often named Margaret in retellings—represents a kind of social contradiction. She is wealthy, educated, and legally protected in some ways, yet still constrained by expectations. Her marriage to an older planter is portrayed as transactional: a match arranged to secure family status and property, not intimacy or companionship.

When her husband dies soon after the wedding, her situation becomes even more complicated. In some versions, she is described as inexperienced in marriage and isolated within the plantation household. She inherits land, money, and authority—but also inherits a structure built on violence she did not create and cannot easily dismantle.

This is where many retellings drift into melodrama. The more important point is structural: even a person who feels trapped by social rules is still operating from a position of power when enslaved people are involved. Her discomfort does not equal the enslaved person’s lack of agency. These are not comparable burdens.

The “Secret” That Reframes the Purchase

The story then introduces another layer: the enslaved man she buys is said to have a connection to her late husband—an illegitimate child, or at minimum a person tied to the planter’s past. That claim is used to explain why she pays such a high price and why she insists on bringing him to her property instead of allowing him to be sent elsewhere.

Whether or not this specific relationship is historically provable, the broader pattern is well documented in slavery’s history: enslavers frequently exploited enslaved women, and children born from those abuses were often kept in bondage. Those children could be sold, inherited, or used as labor, even when biological ties were obvious.

So the “shock” is not that an enslaver might have a hidden child. The shock is that the system allowed such a reality to exist without consequence for the powerful—and with lifelong consequences for everyone else.

A Conversation That Exposes the Core Truth

When the widow speaks to the man she purchased, the story pivots from spectacle to moral tension.

She may believe she has “rescued” him from a worse buyer. She may promise he won’t be sold again, that he will work indoors, that he will be treated differently. She might even believe that restraint and kindness are forms of help.

But the man’s response—again, in many versions—cuts to the center:

Buying a person is not rescue. It is still ownership.

Even if she intends to reduce harm, the relationship remains defined by a legal imbalance. If she can decide where he lives, what he does, and whether he can leave, then his safety depends on her mood, her reputation, and her willingness to keep choosing him over her social standing.

This is one of the hardest truths of slavery to face: a system can absorb individual good intentions and still remain fundamentally violent. Personal kindness cannot cancel structural domination.

Education as a Quiet Form of Resistance

A more grounded part of the narrative is the shared space of reading and learning. Enslaved people were often forbidden to read, precisely because literacy created options: planning, connection, self-definition, and the ability to challenge lies written into law.

In the story, books become a private refuge—something that creates a bridge between two isolated people. For the widow, it’s a way to confront moral reality. For the enslaved man, it’s a way to reclaim personhood in a world trying to reduce him to a function.

But even this “intellectual bond” sits inside a trap. Education can strengthen the spirit, but it does not dissolve the legal chains. It can expose injustice, but it does not automatically produce safety.

When the Story Tries to Become a Romance, History Says “No”

Many viral versions push toward a forbidden-love plot. That framing is where ethical storytelling must draw a hard boundary.

In slavery, consent is structurally compromised. When one person is legally owned by another—when punishment, sale, and confinement are always possible—there is no equal ground. A relationship might contain feelings, dependence, and longing, but it cannot be treated as a conventional romance, because the conditions are not free.

This isn’t about judging emotions. It’s about recognizing reality: slavery polluted every relationship it touched. It forced people to make choices under threat. It turned private life into property management. It made intimacy, family, and trust dangerous.

So the most truthful line in the source text is also the most important historical lesson:

You cannot love someone and own them. The two are incompatible.

The “Ending” as a Social Mechanism, Not a Plot Twist

The final beats of the story—an ultimatum, separation, disappearance, a fire, a buried secret—function like a gothic ending. But they also reflect something historically consistent: powerful communities protected themselves.

Plantation societies were built on reputation and control. Any scandal that threatened the legitimacy of slavery—especially anything suggesting blurred boundaries between “owner” and “enslaved”—could be treated as a crisis. The solution was often silence, removal, and destruction of evidence, not truth.

Whether or not a specific plantation burned in this specific case, the impulse to bury stories was real. Slavery depended on public narratives: that it was orderly, justified, “civilized.” Anything that revealed its moral rot had to be contained.

What This Story Is Really About

If you remove the sensational packaging, what remains is a tragedy about systems, not just individuals.

It is about how slavery turned reproduction into profit.

It is about how society punished women for breaking etiquette while excusing the buying and selling of human lives.

It is about how “help” can still be control when the law makes one person’s freedom depend on another person’s choices.

And it is about how the institution corrupted every human connection, making even tenderness unstable and unsafe.

The correct takeaway is not a scandal, and not a romance. The takeaway is a warning about power: when a system grants one person ownership over another, it destroys the possibility of equality—no matter how complicated the feelings become.

Sources

- Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and the economics of slavery (Encyclopaedia Britannica)

- Slave narratives and the realities of family separation (Library of Congress: Born in Slavery)

- Historic context on slave markets and auction practices (National Park Service: African American Heritage)