On the morning of September 14th, 1862, in a small fishing village called Marble Head on the Massachusetts coast, two Black children sat facing a white physician who had traveled almost 40 miles from Boston just to meet them. His name was Nathaniel Warren. At 53, he had spent his entire career studying the human mind at Harvard Medical School. He had evaluated hundreds of patients, published papers in medical journals across America and Europe, and encountered cases most people would dismiss as impossible. Still, he had never seen anything like the Carter twins.

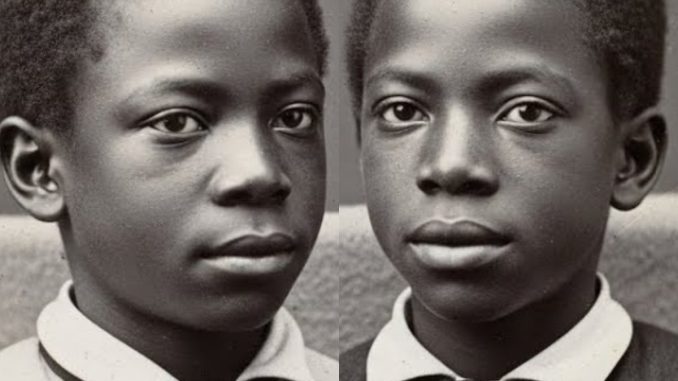

The children were eight. Their names were Elijah and Ruth. They sat perfectly composed in wooden chairs, hands folded neatly in their laps, dark eyes fixed on the doctor with an intensity that unsettled him. They didn’t fidget. They didn’t glance away. They simply watched—almost as if they were the ones assessing him.

Dr. Warren opened his leather bag and pulled out a stack of cards. Each card held a different math problem. He had designed them himself, arranged from simple to extreme. The first were basic addition. The last contained calculations many university professors would struggle to solve without writing anything down. He handed the first card to Elijah.

“Tell me the answer,” Dr. Warren said.

Elijah looked at the card for perhaps half a second.

“23,” he replied.

Correct. The doctor handed him the second card. Elijah answered before the doctor’s hand had even fully pulled back.

“57.”

Correct again. Card after card, the problems became more complex. Addition shifted into subtraction. Subtraction became multiplication. Multiplication moved into division. Soon the cards required multiple operations and layered steps. Elijah answered every one. No pause. No hesitation. Not a single mistake. When they reached the final card—a problem Dr. Warren had needed nearly three minutes to solve when he created it—Elijah studied the numbers for perhaps two seconds.

“439,” he said.

Dr. Warren froze. He checked his answer key. Then checked it again.

“That is correct,” he said, his voice barely above a whisper.

Then he turned to Ruth and removed a different bundle from his bag. Not math this time—pages of text copied from books he had selected precisely because no child should recognize them. One page came from a medical text written in Latin. Another was a legal document filled with archaic phrasing. A third was from a dense philosophical treatise using vocabulary far beyond what an eight-year-old was expected to handle.

He handed the Latin page to Ruth.

“Read this,” he said.

Ruth stared at the sheet. She did not know Latin. She had never studied it. She had never even seen Latin printed on a page before this moment. But as her eyes moved over the words, something shifted. She began sounding them out slowly, then with growing confidence. Her pronunciation wasn’t flawless, but it was recognizable. And more astonishing—after reading each sentence aloud, she paused and offered a careful guess about what it meant, drawing from patterns she noticed in the words. Several of her guesses were correct.

Dr. Warren leaned back, hands shaking. In thirty years of medical practice, he had never witnessed anything like it. He had heard stories about children with extraordinary abilities, but he had always assumed they were exaggerations or tricks. This was neither. He glanced at the twins’ mother, Sarah Carter, standing in the corner of the small room, watching with an expression that held pride—and fear.

“Mrs. Carter,” he said, “how long have your children been able to do these things?”

Sarah Carter was 31, born free in Massachusetts—the daughter of a Black sailor and a Native American woman. She had spent most of her life working as domestic help: cleaning houses and washing clothes for white families who paid her barely enough to survive. She had known her children were different since they were three. That was when Elijah started counting everything he saw, adding and multiplying numbers from daily life, arriving at totals Sarah herself couldn’t verify. That was when Ruth began memorizing entire books after hearing them read aloud only once—reciting passages word for word weeks later as if they were etched into her.

Sarah had tried to keep their abilities hidden. She understood, in a way many white people could not, how dangerous it could be in America for Black children to seem “too” intelligent. In 1862, the country was at war. The Civil War had begun in April 1861, and eighteen months later it showed no signs of ending. Abraham Lincoln had not yet issued the Emancipation Proclamation. In the South, four million Black people remained enslaved. In the North, free Black people lived in an uneasy middle space—tolerated, not embraced; free, yet not treated as equal. A Black child who could read drew suspicion. A Black child who could outthink white adults threatened assumptions many people relied on.

For five years, Sarah kept the secret. She told the twins again and again: never show what you can do. Act ordinary. Hide your gifts. But secrets rarely stay contained. Three weeks before Dr. Warren’s visit, a white merchant named Thomas Aldrich came to Sarah’s small house to deliver fabric she had ordered for sewing work. While Sarah counted coins in the back room to pay him, the merchant noticed Elijah at the kitchen table staring at a newspaper someone had left behind. He laughed.

“Can you even read that, boy?” he asked, his tone heavy with condescension.

Elijah looked up.

“Yes,” he said. “And there’s a mistake in the third paragraph. The reporter wrote that Union forces captured 300 Confederate soldiers at the Battle of Antietam. But if you calculate based on the numbers given earlier in the article, it should be 347.”

Thomas Aldrich stared at him. Then he picked up the paper, reread the paragraph, and did the arithmetic. The boy was right. The merchant left without another word. But within days, the story spread through Marblehead. Sarah Carter’s children could read. Sarah Carter’s children could calculate. Sarah Carter’s children had minds people couldn’t explain.

Dr. Warren heard the story through the usual chain—colleague to patient to neighbor—and initially dismissed it as rumor. Yet something about it kept pulling at him. So he traveled to Marblehead. Now he sat across from two children who had just challenged everything he believed he knew about the mind.

“Mrs. Carter,” he said again, “I have to know. How long has this been true? And how is it possible?”

Sarah looked at her children, then at the doctor. She understood that whatever she said next could reshape their lives.

“They’ve always been this way,” she said. “Since before they could walk, before they could speak. They see what other people don’t see. They understand what other people don’t understand. I don’t know why. I don’t know how. I only know it’s real.”

Dr. Warren nodded slowly. He was already forming the letter he would send to colleagues at Harvard. Already imagining new examinations, papers, lectures. He did not notice the fear in Sarah’s eyes. He didn’t understand what it meant to make her children visible in a world that punished Black people for being seen.

The story of the Carter twins spread faster than Sarah feared. Within a week, three more doctors arrived to test the children. Within two weeks, a reporter from the Boston Evening Transcript showed up with questions and a notebook. Within a month, newspapers across New England carried versions of the story. The headlines differed in tone. The Boston Evening Transcript ran: “Remarkable Negro Children Display Unusual Mental Faculties.” The article sounded cautiously impressed, describing the twins’ abilities while carefully avoiding any implication of racial equality. The Springfield Republican framed it differently: “Scientific Mystery: How Can Such Minds Exist in Such Bodies?” It treated the twins like curiosities, not children. The Providence Journal went further still, calling them “Nature’s Impossibility Made Manifest,” implying their talents must be a rare biological fluke that proved nothing about Black capability in general.

But other reactions appeared. The Liberator, the abolitionist newspaper published in Boston by William Lloyd Garrison, put the twins on its front page. Its headline was blunt: proof of human equality. The article argued the Carter twins showed what abolitionists had long insisted—that perceived differences were shaped by circumstance and access to education, not biology. That piece changed everything. Garrison was famous. He had published The Liberator since 1831; anti-slavery activists read it across the country and abroad. When he wrote about the twins, people listened. Donations arrived at Sarah’s home. Letters came from strangers offering help. Tutors and schools offered instruction at no cost. Churches and lecture halls invited the twins to appear before audiences.

But darker things arrived as well. Threatening letters appeared in the mail, warning Sarah her children would be harmed if they kept attracting attention. At night, stones shattered her windows. A dead animal was left at her door with a note: “Know your place.” Neighbors who had once been cordial now crossed the street to avoid her. Customers suddenly found other seamstresses. White families who had hired her for domestic work let her go one by one until she had no income.

Sarah understood what was happening. Her children’s intelligence disrupted the “order” many white people took for granted. Marblehead had tolerated a Black family as long as that family remained dependent and non-threatening. But the twins suggested something many could not accept: that Black minds could match white minds. That possibility threatened the logic people used to justify slavery and discrimination. It challenged the story they told themselves. So they tried to destroy what they couldn’t explain.

In November 1862, Sarah made a decision that broke her heart. She sent Elijah and Ruth away. Dr. Warren had arranged for them to enroll at the Institute for Colored Youth in Philadelphia. Founded in 1837 by Quaker Richard Humphreys, it was one of the few institutions offering advanced education to Black students. The school agreed to take the twins on full scholarship, with room and board supported by a wealthy abolitionist family. Sarah could not go. She had no money for travel and no way to support herself in Philadelphia. And she knew leaving Marblehead meant losing what little stability she had built—the rented house, her few possessions, the fragile life she had fought to hold together. So, on a cold November morning at Marblehead Harbor, she said goodbye.

She hugged them tightly and spoke words she had never allowed herself to say before.

“You are special,” she whispered. “Not because of what your minds can do. You are special because you are my children. Because you’re good and kind and strong. Because you’ve survived a world that didn’t want you to.”

She pulled back, studying their faces as if trying to store every detail forever.

“The world will try to use you,” she said. “White people will want to parade you in front of crowds. They will want to study you like you’re not human. They’ll want to prove their theories about race, either way, using you as an example.”

She took their hands.

“Don’t let them,” she said. “You’re not evidence. You’re not specimens. You’re not here to prove anyone’s ideas. You are human beings. You deserve to be treated like human beings.”

Elijah and Ruth boarded the ship bound for Philadelphia. They stood at the rail and watched their mother shrink into the distance until she vanished. They didn’t cry. At eight years old, they had learned crying rarely changed outcomes. They watched. They remembered.

The Institute for Colored Youth sat on Lombard Street in a Philadelphia neighborhood shaped by generations of free Black families. The school occupied a three-story brick building that had once been a warehouse, its rooms repurposed into classrooms with donated desks, chairs, and shelves of books collected over decades. When the twins arrived in December 1862, the Institute had about 120 students ages six to twenty-two. Most were children of free Black Philadelphians. Some were people who had escaped slavery via the Underground Railroad. All were there for one reason: to receive an education the broader white society would rather deny them.

The principal was Ebenezer Bassett, 38, a graduate of Connecticut State Normal School and among the first Black Americans to receive formal higher education. He had led the Institute since 1857, shaping it into one of the finest Black educational institutions in the country. When he met the twins, he tested them too—but differently than Dr. Warren. He didn’t care about flashy calculations or memory stunts. He cared about understanding. He sat with them and asked questions about the world.

“Why do you think this country is at war?” he asked.

Elijah and Ruth glanced at each other. They had learned to communicate without speaking; a look could carry an entire exchange. Ruth answered first.

“Because people believe things that aren’t true,” she said. “They believe some people are worth more than others. They believe skin color tells you what a mind is capable of. They believe it because it helps them do cruel things without feeling ashamed.”

She paused.

“The war is about slavery,” she continued. “But slavery is about belief. If people stopped believing Black people were inferior, slavery couldn’t survive. The war is really about what people choose to believe.”

Mr. Bassett leaned back. He had taught for years and met many bright students, but he had never heard an eight-year-old speak so clearly about something so complex.

“And you, Elijah?” he asked. “What do you think?”

Elijah considered the question carefully.

“My sister is right,” he said. “But there’s more. It’s also about money. Slaveholders are rich because they don’t pay for labor. If slavery ends, they lose wealth. People will do almost anything to keep wealth.”

He met Bassett’s gaze.

“I think the war won’t end until one side can’t afford to fight anymore,” he said. “And I think many people will die before that happens.”

Bassett understood why Dr. Warren had been shaken. The twins didn’t just have sharp minds—they had depth, clarity, and perspective beyond their years. But Bassett also understood what the doctor had missed: these children were in danger. Their intelligence made them valuable to some and threatening to others. They would be pursued and exploited. Praised and hated. Rarely allowed peace. Bassett decided in that moment he would protect them, educate them, and prepare them—not just to learn, but to survive.

The years at the Institute transformed Elijah and Ruth. They studied mathematics under Octavius V. Catto, a young Black educator who would later become a major civil rights leader in Philadelphia. They studied literature with Fanny Jackson Coppin, who would later become a pioneering Black woman leader in higher education. They learned science, history, languages, and philosophy from some of the finest Black educators of their era. But above all, they learned control. Bassett believed raw brilliance without wisdom could invite danger. He had seen talented Black students become targets. Elijah and Ruth would need judgment, restraint, and the ability to decide when to reveal their skills and when to disappear into plainness.

“Your minds are like weapons,” he told them one evening. “A weapon always displayed invites attack. A weapon kept hidden can be used at the right moment.”

He leaned forward.

“There will be moments you must show what you can do. Powerful people may need to see it. But there will also be moments when showing it will only harm you. You must learn the difference.”

The twins listened. They had already learned the hard version of that lesson in Marblehead. They practiced hiding in plain sight. They learned to answer correctly, but not too brilliantly. To show knowledge without triggering fear. To read white reactions and adjust accordingly. It was exhausting. It was humiliating. It was necessary.

Meanwhile, the war continued. In January 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring enslaved people in Confederate states free. Philadelphia’s Black community erupted in celebration—church bells, services of gratitude, people in the streets. For the first time, the federal government had declared slavery wrong. But reality tempered the joy. The proclamation didn’t free enslaved people in border states loyal to the Union. It didn’t grant full citizenship. It didn’t end the war. The fighting continued through 1863 and into 1864, and the casualty lists grew. Names like Gettysburg and Vicksburg became symbols of loss on a scale Americans had never experienced.

Elijah followed the war obsessively. He collected newspapers, drew maps of troop movements, calculated casualties and supply constraints, and predicted battle outcomes with startling accuracy. In March 1864, when he was ten, he wrote a letter to Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, commander of the famous 54th Massachusetts Infantry, one of the first Black regiments in the Union Army. Shaw had been killed at Fort Wagner in July 1863, but Elijah did not know that. The letter was returned with a note explaining the colonel was dead. Yet someone had read the letter first—someone impressed enough to share it.

Elijah’s letter analyzed strategy. He argued the Union would win only if it prioritized cutting Confederate supply lines instead of simply taking territory. He recommended expanding the role of Black soldiers—not only for manpower, but for commitment. He predicted the war could end in 1865 if those approaches were followed. The letter reached a Boston editor who had known Shaw and was published under the headline: “A Child’s Wisdom on the War.” Once again, the Carter twins appeared in newspapers. Once again, danger followed.

In April 1864, five white men came to the Institute. They wore expensive suits and spoke with Southern accents. They claimed to be businessmen from Maryland, a border state where slavery was still legal, and said they had heard about “remarkable” children and wished to meet them. Bassett met them at the door and felt his instincts tighten. They looked like men who hunted human beings for profit.

“The children you’re asking about are not fugitives,” Bassett said. “They were born free in Massachusetts. They’re here legally under my protection and this institution’s support.”

The leader—a tall man with gray beard and cold eyes—smiled without warmth.

“We’re not accusing them of anything,” he said. “We only want to meet them. A brief visit, surely, would do no harm.”

“The children are not available,” Bassett replied. “They are students. And I do not believe your interest is academic.”

The men exchanged glances—silent, coordinated, unsettling.

“Very well,” the leader said. “Perhaps we’ll return another time.”

They left. But Bassett knew they would not stop. That night he called Elijah and Ruth into his office.

“Do you know who those men were?” he asked.

Ruth answered first. “Not businessmen,” she said. “They looked at us the way buyers look at merchandise. They want something.”

Elijah added quietly, “And they weren’t from Maryland. Their accents didn’t match. One used a phrase common in South Carolina.”

Bassett believed them.

“I think they may try to take you,” he said. “Children with minds like yours could be worth money to the wrong kind of people—men who want to study you, display you, or worse.”

He paused.

“I’m sending you somewhere safer,” he said. “There’s a community in Ohio near a town called Oberlin. It’s strongly abolitionist. The college has admitted Black students for years. There’s a network there that protects people in danger. You’ll be safer.”

Two days later, the twins boarded a train heading west. They didn’t know it then, but they wouldn’t return to Philadelphia for years. They would never see Bassett again, and the men in suits would not stop searching.

The trip took four days. The twins traveled with a woman who called herself Harriet Tubman—not the famous conductor of the Underground Railroad, but someone using the same name, a common practice in the freedom network. Borrowing well-known names created confusion and cover. This Harriet was 40, strong-handed, watchful, and quiet. She spoke little, but she observed everything. She made sure no one followed. They traveled by train when it was safe and by wagon when it was not. They stayed in homes marked by subtle signals in windows—signs indicating protection for Black travelers. They ate meals prepared by strangers who asked no questions and expected nothing in return.

On the third night, in a farmhouse in western Pennsylvania, Harriet sat with them and told them bluntly what they needed to know.

“You are being hunted,” she said. “Not just by those men at your school. Others have heard about you. People who want to use you.”

Her eyes carried a heaviness that suggested experience.

“Some want to study you,” she continued. “They want to prove their ideas about race and intelligence. They don’t see you as children. They see you as objects.”

Ruth felt cold fear rise in her chest.

“Others want to display you,” Harriet said. “Put you on stages, charge money to stare at you, dress you up, teach you tricks, and call it science or entertainment.”

Elijah’s fists tightened.

“And some,” Harriet said quietly, “want to erase you. They believe your existence threatens everything they claim is true. They would rather destroy you than let you prove them wrong.”

She leaned forward and took their hands.

“This is the world you live in,” she said. “I’m sorry. I can’t promise it will become easy. I can promise there are people who will help you—people who believe in freedom and will protect you.”

She stood.

“Tomorrow we reach Ohio,” she said. “You’ll be safer there. But remember what I told you. Never forget you are being watched, and never stop being careful.”

That night the twins didn’t sleep. They lay staring at the ceiling, thinking of their mother alone in Marblehead, unaware where they were. Thinking of Bassett, who had protected them then sent them away to protect them more. Thinking of the men who wanted them. Thinking of the future—long, uncertain, dangerous. They were ten years old and already understood what no child should: that their gifts could be treated like a danger.

But they understood something else too. They had each other. Born together, raised together, sharpened together. Their minds worked differently when side by side. A glance between them could carry full meaning. They could divide problems between their perspectives and solve faster than either could alone. Their secret wasn’t only intelligence. It was the bond that made them stronger together than apart. And as long as they held that bond, they believed they could survive.

Part two.

Oberlin, Ohio was unlike any place Elijah and Ruth had ever seen. Founded in 1833 by Presbyterian ministers who believed racial equality was a Christian duty, the town welcomed Black residents, Black students, and people escaping slavery. Oberlin College was among the first in America to regularly admit Black students and women alongside white men. By 1864, when the twins arrived, Oberlin had become one of the most integrated communities in the United States.

They were placed with the Langston family. John Mercer Langston was a Black lawyer educated at Oberlin and one of Ohio’s most prominent Black leaders. His wife, Caroline, was a teacher who ran a small school for Black children in their home. They had three children of their own and welcomed Elijah and Ruth like family. For the first time since leaving Marblehead, the twins felt something close to safety. But they would learn that safety was often temporary.

The first months focused on schooling. The twins enrolled in Oberlin’s preparatory department, where students as young as ten could begin academic work leading toward college. The curriculum was demanding, intended to prepare students for the kind of education offered to white students at Harvard or Yale. For most students it was difficult. For Elijah and Ruth it wasn’t enough. Within weeks, teachers saw what Dr. Warren and Bassett had seen: these were not ordinary students. They absorbed information at an astonishing pace. They linked ideas across subjects in ways their instructors hadn’t considered. They asked questions that revealed understanding far beyond their years.

The head of the preparatory department, Professor Mary Jane Patterson, called them to her office after their first month. Patterson was remarkable in her own right. Born free in North Carolina, she moved to Ohio as a child and, in 1862, became the first Black woman in the United States to earn a bachelor’s degree, graduating from Oberlin with honors. She understood better than most what it meant to be Black and brilliant in a society that refused to honor Black excellence. She sat behind her desk and studied the twins closely.

“Your teachers have reported your progress,” she said. “They’re astonished. They’ve never taught students like you. They don’t know how to place you.”

The twins waited quietly.

“I’ve reviewed your examination results,” Patterson continued. “You’ve mastered material meant for students twice your age—in weeks. If you continue, you’ll exhaust our curriculum in a year or two.”

Her tone turned serious.

“This creates a problem,” she said. “Not for you—for us. We don’t have the resources to educate minds like yours. We don’t have enough teachers or advanced texts to keep you challenged.”

Ruth spoke first. “What do you suggest?”

Patterson’s stern face softened into the hint of a smile.

“I suggest we stop treating you only as students,” she said. “And begin treating you as colleagues.”

It was unusual, perhaps unprecedented, but Patterson had authority—and she used it. In their second month, Elijah and Ruth were given broad access to the college library. They attended lectures meant for older students. They pursued whatever subjects fascinated them and were encouraged to share their findings with faculty.

Elijah gravitated toward mathematics and military strategy. He studied Napoleon’s campaigns, ancient generals, logistics, troop movements, supply systems. He applied math to warfare, developing theories about optimal deployment and resource allocation that professors found striking. Ruth gravitated toward languages and history. She taught herself Greek and Hebrew in addition to the Latin she had begun. She read primary sources in original languages and caught nuances lost in translation. She became especially drawn to the history of slavery, tracing it back through ancient civilizations and studying how systems of bondage evolved over centuries.

Still, even in Oberlin, the twins couldn’t escape the truth: people were still searching. In March 1865, a stranger arrived asking questions. He was a white man in his forties, polished and well-dressed, speaking like someone educated and wealthy. He introduced himself as Dr. Samuel Morton, a scientist from Philadelphia studying human intelligence. He said he’d heard about two exceptional children and wanted to meet them “for academic purposes.”

He was lying. The real Dr. Samuel Morton had been a Philadelphia physician who collected skulls and measured them to promote racist theories claiming white superiority. And he had died in 1851—fourteen years before this man appeared. John Mercer Langston recognized the deception quickly. He confronted the stranger at his hotel.

“I don’t know who you are,” Langston said. “But I know who you’re not. Dr. Morton is dead. And I know what you want. You want those children. You will not have them.”

The man’s polite mask slipped. His face twisted into something hard.

“Those children are valuable,” he said. “More valuable than you understand. There are people who will pay heavily for minds like theirs—and others who will pay heavily to make sure minds like theirs are never seen again.”

He stepped closer, voice low.

“You can’t protect them forever,” he said. “Sooner or later, they’ll leave Oberlin. Sooner or later, they’ll be exposed. And when that happens, we will be waiting.”

He walked away, leaving Langston with a cold fear he could not shake. That night Langston told the twins everything. He didn’t soften the truth. He believed they deserved the full reality.

Ruth listened calmly, though her emotions churned beneath the surface.

“Who are they?” she asked. “Who’s paying them?”

Langston shook his head.

“I can’t say for certain,” he said. “But I suspect wealthy men from the South who built fortunes from slavery. The war is turning against them. They know slavery will end. They’re looking for ways to preserve the idea that, even without chains, Black people should remain beneath them.”

He paused.

“Children like you threaten that idea,” he said. “Some want to study you to find an explanation that protects their beliefs. Others want to erase you before you can prove them wrong.”

Elijah had been silent until then. Now he asked, steady-voiced, “What can we do?”

Langston looked at him with respect. This eleven-year-old was not asking how to hide. He was asking how to respond.

“For now, keep learning,” Langston said. “Knowledge is power. The more you know, the stronger you become. But you must be careful. Don’t draw unnecessary attention. And be ready to move the moment danger grows too close.”

The twins nodded. They understood. They had been running since they were eight. They would keep running as long as they had to. But somewhere inside them, they knew running would not always be enough.

The war ended on April 9th, 1865, when General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House. The news reached Oberlin three days later. Bells rang. People filled the streets celebrating, crying, embracing strangers. After four years and more than 600,000 deaths, the war was over. The Union stood. Slavery was destroyed.

But celebration didn’t last. Five days later—April 14th, 1865—President Lincoln was assassinated at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. He died the next morning. The news threw a shadow over everything. The man who had guided the nation through crisis, who had issued the Emancipation Proclamation, was gone. Andrew Johnson took his place—his commitment to Black equality uncertain at best.

Ruth understood immediately what Lincoln’s death could mean.

“Lincoln was the only thing protecting us,” she told Elijah that night. “Without him, everything changes.”

Elijah agreed. His study of war had taught him that winning was only the beginning.

“The people hunting us will be stronger now,” he said. “They’ll find allies. They’ll have time to rebuild. And they won’t forget.”

He was right. Reconstruction became a time of both hope and terror. Amendments abolished slavery, granted citizenship, and promised voting rights. Black men were elected to Congress. Black communities built schools and churches. For a moment, equality seemed within reach. But violence against Black people surged. White supremacist groups terrorized families and murdered leaders. Laws and intimidation restricted freedom in everything but the most technical sense. Elijah and Ruth watched history unfold with widening eyes. As teenagers, their minds grew sharper and their understanding deeper than most adults’. They realized the struggle had not ended. It had barely begun.

In 1868, when the twins were fourteen, they made a choice that would shape the rest of their lives: they would use their gifts in service of their people. The decision came after long conversation with Langston, who had become like a father. Langston had been appointed the first dean of the law department at Howard University in Washington, D.C. He was preparing to move and wanted them with him. Howard, founded in 1867, existed to provide higher education for Black Americans. It was small and underfunded, but it represented something powerful: the right to Black intellectual development at the highest level. Langston believed the twins belonged there—not as students, but as contributors.

“You’ve learned everything Oberlin can offer,” he told them. “Your minds are ready for work that matters. Howard needs people like you.”

Ruth hesitated. Fourteen—and teaching adults? Langston smiled.

“You won’t teach in the usual way,” he said. “You’ll work as researchers. You’ll help faculty projects. You’ll write papers that will be published under other names. Your work will be hidden, but it will be real.”

He leaned in.

“This is how influence works,” he said. “Quietly. You will shape the thinking of those who shape the world. You will plant seeds that become forests—and no one will know where the seeds began.”

They understood. It wasn’t fame. It was purpose. They agreed.

But before they left, news arrived that overturned everything: their mother was dying.

Sarah Carter had never recovered from losing her children. After they left Marblehead, she sank into poverty and despair. The white community continued to shun her. The few Black families nearby helped where they could, but resources were scarce. She developed consumption—what would later be called tuberculosis. By the time Oberlin received word, she had been ill for months. Doctors said she had weeks, perhaps less. The twins faced a brutal choice. Returning to Marblehead meant exposing themselves to people who had hunted them for years. Those men might still be watching. But their mother was dying, alone, after sacrificing everything for them.

They didn’t hesitate. They boarded a train heading east.

The trip took three days. They traveled under assumed names, dressed plainly, looking like ordinary Black children. They avoided eye contact, spoke as little as possible, tried to disappear. But disappearing has limits. On the second day, as the train crossed Pennsylvania, Elijah noticed a man watching them across the car. White, middle-aged, weathered like a laborer—yet his eyes were too sharp, too calculating. Not what he seemed. Elijah leaned toward Ruth and whispered without moving his lips.

“We’re being watched,” he said. “Brown coat by the window.”

Ruth didn’t turn. She had already noticed.

“I know,” she whispered. “And there’s another at the front. They’re together.”

Elijah ran through options. Get off at the next station? It might only delay. Hide in a crowd? There wasn’t much of one in rural stops. Fight? Two teenagers against grown men, likely armed.

“The train is slowing,” Ruth said. “We reach a station in about three minutes. When doors open, we run.”

Elijah gave the smallest nod.

The three minutes felt endless. The train slowed. The landscape shifted toward a small town. The man in the brown coat stood and drifted toward them. The man at the front did the same. Closing in. The train stopped. Doors opened. The twins surged forward—fast, lean from years of living alert. They burst onto the platform, weaving through passengers. Behind them came shouts as the men pushed after them. The twins didn’t look back. They ran through the station, past the ticket counter, into the town’s main street. They didn’t know where they were. They didn’t know where to go. They just ran.

A hand grabbed Ruth’s arm. She spun, ready to fight or cry out. But it was a Black woman—older, perhaps sixty, gray hair, kind eyes, dressed like a domestic worker. Her grip was strong.

“This way,” the woman said. “Quickly—before they see you.”

No time for questions. The twins followed her down an alley, through a gate, into a small yard behind a house. She opened a cellar door and motioned them down. They descended into darkness. The door shut above. Silence.

Later—minutes that felt like hours—the cellar door opened. The woman came down with a lantern.

“You’re safe for now,” she said. “They searched the station, but they didn’t find you. They boarded another train heading farther east. They think you’re still running.”

Ruth finally asked, “Who are you? How did you know to help us?”

The woman smiled.

“My name is Patience,” she said. “I work for the family here. I knew to help because I was told to watch for two children who might need protection. A message came last week from a man named Langston. He said you might pass through. He told me to keep you safe.”

The twins exchanged a look. Even from far away, Langston had planned for them. He had anticipated danger. Help existed along their path. They were not alone.

They hid in Patience’s cellar for two days while she brought food, water, and news. The men were still asking questions, offering rewards for information about two Black children traveling together. But Patience told them something else: their mother was still alive. Sarah Carter had outlasted predictions. She was clinging to life, refusing to let go until she saw her children one more time.

On the third day, Patience arranged a wagon to take them the final miles to Marblehead. They traveled at night, hidden beneath blankets. The driver was a Black man who asked nothing and said little. Just before dawn they arrived at Sarah’s house. It looked smaller than Ruth remembered—paint peeling, windows cracked, garden swallowed by weeds. But the door stood open, and a candle burned in the window.

Inside, Sarah lay on a narrow bed in the corner. She was terribly thin. Hair gone gray. Skin stretched over bone. Eyes closed. But when she heard her children, her eyes opened. And despite illness, poverty, separation—she smiled.

“You came,” she whispered. “I knew you would.”

Elijah and Ruth knelt beside her, one on each side, taking her hands. For the first time in six years, they were together again.

Sarah lived three more days. In that time she told them the stories she had never been able to share—her childhood, her parents, the family history stretching back generations. She told them about their father, a sailor who died at sea before they were born. She told them about the night they arrived in the world and how she knew immediately they were extraordinary. And then she told them what she wanted for their lives.

“Don’t hide,” she said, voice weak but steady. “I told you to hide when you were small. I thought I was protecting you. But I was wrong.”

She squeezed their hands.

“You can’t hide what you are,” she said. “The world will always try to shrink you—put you in boxes—tell you what you cannot do. Don’t listen. Stand tall. Let them see what you are. Show them what Black people can become when given the chance.”

She drew a trembling breath.

“I won’t live to see what you become,” she said. “But I know it will be magnificent. I know you will change the world. And somewhere, somehow, I will be watching.”

She died on the fourth morning with her children holding her hands.

They buried her in a small cemetery outside Marblehead. The grave was unmarked. No minister, no ceremony—only the twins and an undertaker who agreed to help. As they stood over the fresh earth, Ruth spoke the words Sarah would have wanted.

“We won’t hide,” Ruth said. “We won’t pretend. We’ll show the world what you always knew we could be.”

Elijah added his promise.

“We’ll fight,” he said, “not with weapons and not with cruelty—but with our minds. We’ll prove their beliefs are wrong, and we will not give up.”

They stood in silence, then turned away from the grave, away from Marblehead, away from the childhood life that had been taken from them. They were fourteen. They were orphans. And they were ready to change the world.

The twins arrived in Washington, D.C., in the autumn of 1868. The capital was full of contradictions: grand government buildings beside deep poverty; white politicians arguing about Black futures in marble rooms while Black families struggled only blocks away. Freedom had been declared, but equality still felt distant. Howard University sat on a hill overlooking the city—muddy fields, a handful of buildings, but fierce ambition. The twins began work immediately. Officially they were “students,” but it was a technicality. In reality, they worked beside faculty, contributing to research that would shape the future of Black education. Elijah focused on mathematics and economics, developing ideas about how Black communities could build wealth in the face of systemic discrimination. Ruth focused on history and law, documenting slavery’s crimes and building legal arguments for equal rights and repair. Their contributions stayed hidden, as Langston had promised. Papers appeared under professors’ names. Speeches were delivered by others. The twins remained in the background—unseen but influential.

But anonymity has limits. In 1871, when they were seventeen, Ruth wrote a legal brief arguing for federal protection of Black voting rights. A Howard professor put his name on it, but the reasoning was Ruth’s. Republican members of Congress used it to support what became known as the Enforcement Acts—laws designed to combat the Ku Klux Klan and protect Black voters. The laws passed. The Klan was temporarily suppressed. Black voter participation surged in 1872.

Then someone noticed.

A journalist from a Southern newspaper investigated where the arguments came from. He traced the brief back to Howard, discovered the credited professor hadn’t truly authored it, and eventually uncovered the twins. In December 1872, an article appeared under the headline: “Negro Children Control Congress.” It was exaggerated and soaked in racist assumptions, but it exposed a truth: two Black teenagers had helped shape federal policy. The backlash was immediate and dangerous. Congress launched inquiries. Howard was threatened with losing funding. Threats poured in. Men tried to set fire to the building where the twins lived.

But something else happened too. Black newspapers celebrated them. Churches spoke their names. Parents told children about Elijah and Ruth Carter—proof that Black minds could equal any minds. The twins had spent years hiding. Now, finally, they stepped into public view.

In January 1873, Elijah and Ruth gave their first public speech at Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church in Washington, D.C. The church overflowed—people standing in aisles, sitting on sills, crowding outside to listen through open doors. The twins walked to the front and faced a sea of Black faces waiting for their words.

Ruth spoke first.

“They told us we couldn’t think,” she said. “They told us our minds were lesser. They told us slavery was justified because we were less than human. They said it because they wanted to believe it—because believing it made cruelty easier.”

She paused.

“We are proof they were wrong,” she said. “Not because we are unique—because we were given opportunity. The chance to learn. The chance to develop what was already inside us.”

She gestured to the crowd.

“Everyone here has the same capacity. Every Black child in America has that potential. The difference is opportunity. That is what we must fight for—not only freedom, not only legal equality, but the chance for every child to discover what their mind can do.”

Elijah followed.

“Our mother told us before she died not to hide,” he said. “She told us the world will try to make us smaller, but we must not listen.”

He scanned the faces—hope, pain, determination.

“We’ve been fighting this our whole lives,” he said. “We’ll keep fighting as long as we live. But we can’t do it alone. Every one of you is part of this struggle. Every one of you has a mind to sharpen, a voice to raise, a contribution to make.”

He lifted his fist.

“They want us silent. They want us unseen. They want us to accept the bottom. But we will not be silent. We will not disappear. We will not accept what they tell us we must accept.”

His voice filled the sanctuary.

“We are Elijah and Ruth Carter. We are Black. We are gifted. And we are only the beginning.”

The church erupted. People cried openly. Strangers embraced. For a moment, in that sacred place, equality felt possible. The twins stood together, hands linked, remembering the small Massachusetts village that had tried to swallow them, the years of running, the years of work, the years of hiding—leading to this moment: standing before their people and claiming a place in history. Yet their story was not finished. It was only unfolding.

The decades that followed carried both triumph and hardship. Elijah Carter became a major economist, developing ideas about wealth-building in oppressed communities—work that would not be fully recognized until long after his death. He advised Black business owners, trained accountants, and helped create investment funds that supported generational wealth in a hostile system. Ruth Carter became a legal scholar whose arguments formed early foundations for civil rights strategies that would later reach the Supreme Court. She trained Black lawyers and drafted briefs challenging segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement. She rarely argued in court herself—women were not permitted to do so—but her words were carried by others inside courtrooms across the nation. Together, they helped found schools, newspapers, and organizations designed to carry the work forward.

But there were setbacks. Reconstruction ended in 1877, and with it ended much of the federal commitment to protecting Black rights. White supremacist violence surged again. Jim Crow laws expanded. Progress was dismantled piece by piece. The men who had hunted the twins never fully disappeared. Threats continued—arson attempts, ambushes, intimidation aimed at everyone they cared about. They learned to live with danger like a shadow that never left. And they endured loss: John Mercer Langston died in 1897, leaving a gap that could never be filled. Friends and allies passed away. Communities that once felt safe grew smaller. Still, the twins did not stop.

In 1910, at age 56, they gave their last public speech together at the inaugural conference of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. The NAACP had formed a year earlier, building on decades of work done by people like the Carters. Ruth was frail now, health worn down by relentless labor. Elijah stood beside her, hair white, eyes still sharp.

“We’ve lived long enough to witness change,” Ruth said, voice softer but clear. “When we were born, slavery was law. When we die, we leave behind a generation that has known only freedom. That is progress.”

She paused to breathe.

“But we have also seen how easily progress can be reversed—how quickly freedom can be narrowed—how persistent hatred can be.”

She looked toward the young faces in the audience.

“Do not lose heart,” she said. “Do not surrender to despair. You may not live to see the victory. We will not live to see the victory. But the victory will come—because truth is stronger than lies, and love is stronger than hate.”

Elijah spoke last.

“Our mother told us to show the world what Black people can become when given the chance,” he said. “We tried to do that. We succeeded in some ways and fell short in others. But we never stopped.”

He took Ruth’s hand.

“Now the work belongs to you,” he said. “Continue what we began. Build on what we built. Do not give up. Do not surrender. Do not accept the world as it is when it can become better.”

He looked out one final time.

“We are Elijah and Ruth Carter. They said our minds were impossible. We proved nothing is impossible. And we pass that lesson to you—now and always.”

Ruth died three months later, in the spring of 1910. Elijah followed in the autumn of that same year. They were buried side by side in Washington, D.C., not far from Howard University. Their headstone carried a simple inscription:

“Two minds, one purpose. Freedom.”

Over time, the story of the Carter twins faded from popular memory. History books centered other names and other moments. Their work became part of a wider civil rights narrative, their personal identities swallowed by the movement. But their legacy remained. Every Black child who gained access to education, every Black lawyer who argued for justice, every Black economist who helped build community wealth, every family that rose from poverty through learning and labor—each carried something the Carter twins helped ignite.

And somewhere inside Howard University’s archives, boxes still sit unopened: letters, drafts, notes bearing the handwriting of two children who—according to the prejudices of their era—should not have been able to write what they wrote. Proof of minds that “shouldn’t” have existed according to the myths people insisted on believing.

Their story proves something that never should have needed proof: intelligence is not determined by race. Potential is not bound by circumstance. A mind—given the chance—can reach heights that seem impossible. Two children born into poverty, pursued by hatred, made orphans by injustice, can still reshape their world.

And it proves something else, too: the world can change. Not quickly. Not easily. Not without cost. But it can change. That is the lesson of Elijah and Ruth Carter. That is the secret they carried—an “impossible” secret the world tried to deny. The secret was hope. The secret was endurance. The secret was love. And unlike the twins themselves, that secret cannot die. It lives on in every person who refuses to accept limits, in every child who dares to dream, in every mind that reaches for something greater than what the world says is possible.

The Carter twins lit a flame in 1862. That flame still burns today—and it will keep burning as long as there are people willing to protect it, feed it, and believe.