Plimpton 322 Revisited: How Modern Analysis Is Reshaping Our Understanding of Babylonian Mathematics

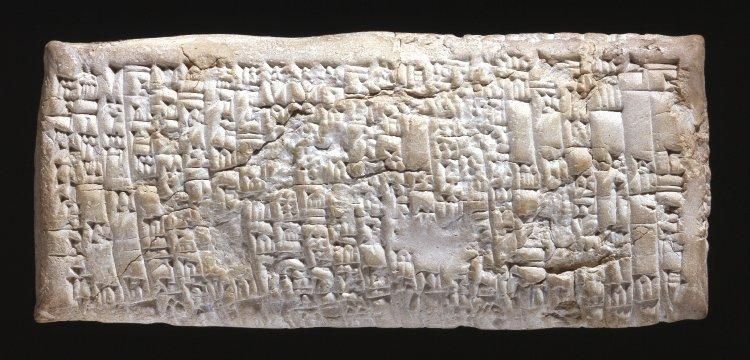

For more than a century, a small clay tablet known as Plimpton 322 has occupied a quiet but important place in the study of ancient mathematics. Measuring roughly five inches by three inches and inscribed with cuneiform symbols, the tablet dates back nearly 3,700 years to the Old Babylonian period. Housed today at Columbia University, it has long fascinated scholars because of the numerical patterns etched into its surface—patterns that appear strikingly advanced for their time.

Discovered in the early 1900s near the ancient city of Larsa in present-day Iraq, Plimpton 322 was acquired by the archaeologist and antiquities dealer Edgar J. Banks. At first glance, it seemed to be one of many administrative or instructional tablets produced by Babylonian scribes. Early interpretations suggested it might have been used for accounting, education, or basic numerical exercises based on the Babylonian base-60 number system.

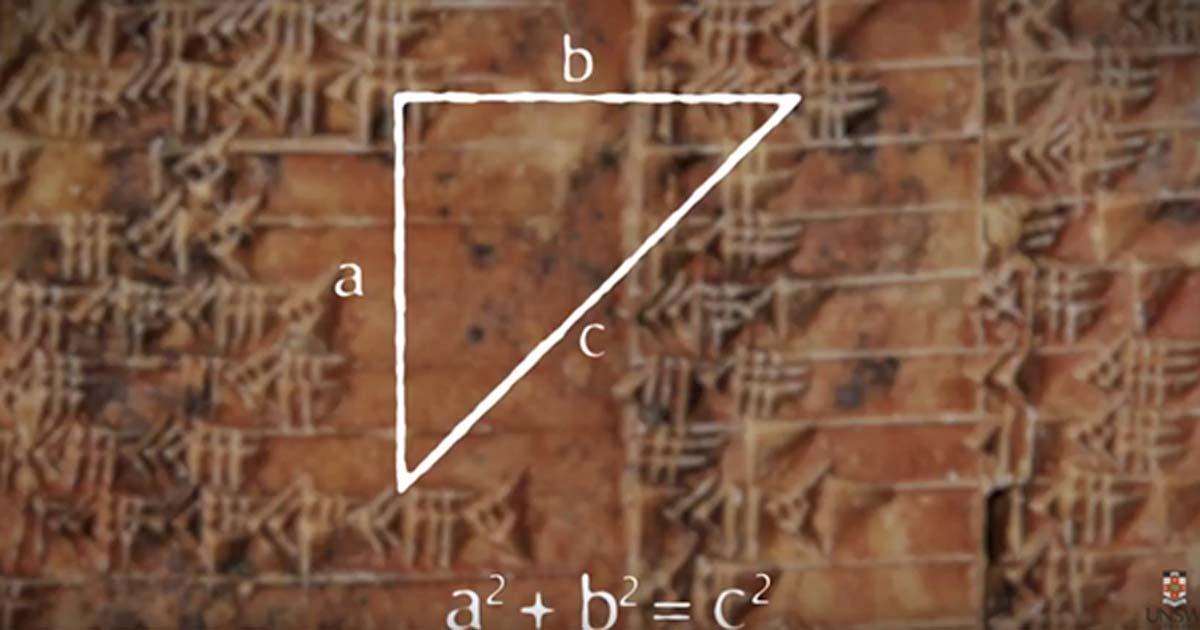

However, as mathematical historians examined the tablet more closely, they noticed something unusual. The numbers did not resemble typical bookkeeping records. Instead, they appeared to describe relationships between the sides of right-angled triangles. These relationships closely align with what modern mathematics identifies as Pythagorean triples—sets of three numbers that satisfy the equation a² + b² = c².

The significance of this observation is that Plimpton 322 predates the Greek mathematician Pythagoras by more than a thousand years. This raised an important historical question: what exactly were Babylonian scholars doing with this mathematical knowledge?

A Long-Standing Academic Debate

For decades, researchers debated the purpose of Plimpton 322. Some suggested it was a teaching aid used to instruct students in advanced arithmetic. Others proposed it was a reference table for surveyors or builders who needed precise ratios when measuring land or constructing buildings.

One influential interpretation came in the mid-20th century, when scholars argued that the tablet listed Pythagorean triples in a systematic order, indicating a structured approach rather than random examples. This implied that Babylonian mathematicians understood geometric relationships conceptually, even if they did not express them using the same theoretical language later adopted by Greek mathematicians.

What remained unclear, however, was why the Babylonians organized the numbers the way they did. The tablet contains 15 rows and four columns, with some sections missing due to damage. The surviving data follows a precise internal logic, but that logic was difficult to fully explain using traditional methods alone.

A New Look Through Computational Analysis

In recent years, advances in computational modeling and pattern recognition have allowed researchers to reexamine ancient mathematical texts with greater precision. High-resolution imaging and algorithmic analysis have been applied to Plimpton 322 to test different hypotheses about how the numbers were generated and why they were arranged as they are.

These tools do not “decode” hidden messages but instead help identify structural patterns that may not be immediately apparent to human readers. When applied to Plimpton 322, computational analysis supports the idea that the tablet functioned as a systematic table of right-triangle ratios.

Unlike later Greek trigonometry, which focuses on angles and relies heavily on approximations, the Babylonian approach appears to have emphasized exact ratios between sides. Working within a base-60 system allowed Babylonian mathematicians to express many fractions precisely, avoiding the rounding errors that can arise in base-10 calculations.

As a result, Plimpton 322 may represent an early form of trigonometric reasoning based on ratios rather than angles. While it does not resemble modern trigonometry as taught today, it demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of geometric relationships tailored to practical applications.

Practical Mathematics in the Ancient World

Babylonian mathematics was deeply connected to everyday needs. Surveying land, constructing temples, managing irrigation systems, and aligning structures all required reliable numerical methods. A table like Plimpton 322 would have been valuable for ensuring consistency and accuracy in such tasks.

Rather than viewing Babylonian mathematics as an early step toward Greek theoretical geometry, many historians now see it as a distinct tradition with its own priorities. Babylonian scholars focused on problem-solving and calculation, developing methods that worked efficiently within their numerical system.

This perspective challenges the traditional narrative that portrays mathematical progress as a linear journey culminating in Greek philosophy. Instead, it highlights the possibility that different cultures developed advanced mathematical ideas independently, shaped by local needs and intellectual traditions.

Reassessing Historical Assumptions

The renewed attention to Plimpton 322 has encouraged historians to reconsider how knowledge is categorized and transmitted. Greek mathematics emphasized proofs and abstract reasoning, which later became central to Western education. Babylonian mathematics, by contrast, emphasized computation, tables, and practical solutions.

Neither approach is inherently superior. They represent different ways of engaging with mathematical reality. Plimpton 322 shows that complex mathematical thinking existed long before formal proof-based systems were developed, even if it was expressed in a different form.

Importantly, scholars caution against overstating the implications. Plimpton 322 does not suggest that Babylonians possessed modern science or technology. Nor does it indicate a lost advanced civilization. Instead, it provides evidence of a highly capable intellectual culture whose achievements were later overshadowed by changes in language, politics, and educational priorities.

Why Knowledge Disappears

One reason Babylonian mathematical traditions did not continue uninterrupted is the fragility of knowledge transmission. Clay tablets survive only under favorable conditions, and literacy in cuneiform was restricted to trained scribes. When political centers declined or educational institutions disappeared, specialized knowledge could fade quickly.

The destruction of archives, changes in language, and shifts in cultural emphasis all contributed to the loss or marginalization of earlier mathematical methods. Plimpton 322 survived largely by chance, offering a rare window into a sophisticated but largely forgotten intellectual world.

The Role of Modern Technology

Modern analytical tools, including computational modeling, have not revealed hidden messages or unexpected technologies within Plimpton 322. What they have done is clarify how carefully structured the tablet is and how intentional its numerical design appears to be.

These tools help historians test competing theories and better understand ancient methods without projecting modern assumptions onto the past. In this sense, technology does not rewrite history but refines it, allowing scholars to ask more precise questions.

What Plimpton 322 Ultimately Tells Us

Plimpton 322 reminds us that ancient societies were capable of complex and innovative thinking. It also highlights how historical narratives can oversimplify the past by focusing on a limited set of traditions while overlooking others.

Rather than questioning history itself, the tablet encourages a broader, more inclusive view of human intellectual development. Mathematics did not emerge from a single source or follow a single path. It evolved in multiple places, shaped by different cultures responding to practical challenges with remarkable creativity.

As research continues, Plimpton 322 will likely remain a subject of discussion—not as a symbol of lost secrets, but as evidence of how much there is still to learn about the diversity of human knowledge in the ancient world.

In that sense, the tablet’s true significance lies not in mystery, but in perspective.