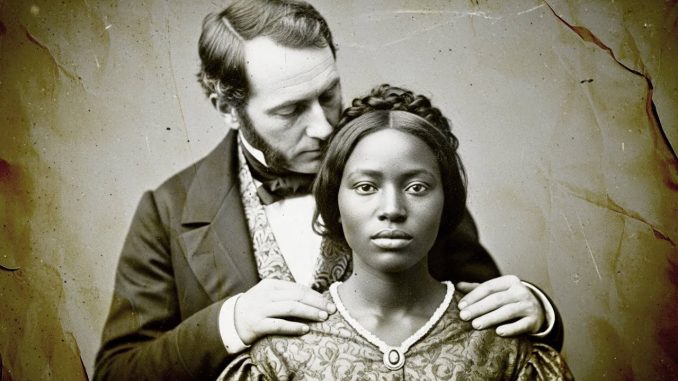

The Planter Who Married an Enslaved Young Woman, Then Learned a Devastating Family Truth: A Mississippi Story From 1839

In the humid Mississippi summer of 1839, a case circulated through Madison County that people discussed in whispers, if they discussed it at all. It involved a wealthy planter, an enslaved young woman, and a marriage that challenged the rigid social order of the time. The story later became difficult to verify in full because many records were lost, destroyed, or never formally created. What remains today is a patchwork of courthouse fragments, plantation accounting books, later oral histories, and a few references preserved by chance.

Because the surviving material is incomplete, historians tend to treat the narrative cautiously. Still, the outline of events—repeated in multiple strands of memory—offers a stark window into how power operated in a society built on human bondage, and how secrecy was used to protect reputations at the expense of truth.

What follows is a reconstruction based on the type of sources often used to study the antebellum South: scattered legal documents, financial records, and testimony collected decades later. Some details may never be confirmed. But the themes are unmistakable: control, silence, and the devastating consequences of treating people as property.

A Plantation World Built on Control

Accounts describe Hyram Callaway as a prominent landowner whose estate, often referred to as Providence in later retellings, sat near fertile riverland and produced large cotton yields. Like many planters of his era, he reportedly kept meticulous records—crop output, livestock health, purchases, repairs, and the forced labor assigned to each enslaved person. These ledgers, where they survive, show a mind committed to classification and command.

In that world, everything was meant to be legible and managed. Yet there were always boundaries that resisted control: weather, disease, market swings, and the constant reality that people under coercion maintained their own inner lives and networks of knowledge.

Local geography also shaped the mythology of the region. Several retellings emphasize a nearby swamp—an area of dense water, cypress, and shadow that plantation owners often described as untamable. Whether or not that swamp played a direct role in the events that followed, it became a powerful symbol in later memory: the place where the “order” of the plantation ended and something older, wilder, and less governable began.

A Marriage That Shocked a Community

The central claim in surviving accounts is that Callaway attempted to formalize a marriage with Eliza, a young enslaved woman who worked in his household. In the legal and social context of 1839 Mississippi, this was not merely unusual. It collided with laws and norms designed to maintain racial hierarchy and preserve the system of slavery.

Some narratives describe a lawyer or relative urging Callaway to reconsider, warning that he risked public backlash and economic consequences. Whether such a letter existed exactly as later retellings describe is difficult to confirm. But it is plausible that anyone in his circle would have recognized the danger: not danger to Eliza, whose lack of rights already placed her at extreme risk, but danger to the planter’s standing among peers.

In several versions, Callaway’s response is described as dismissive. He is portrayed as a man who believed his wealth could override consequences. That attitude—confidence that status could bend reality—appears frequently in planter correspondence more generally, which may explain why the story has endured.

A Ledger Entry With Heavy Meaning

One of the most haunting details repeated in oral tradition involves a ledger line where Eliza’s name was allegedly re-marked from “enslaved domestic worker” to “Mrs. Callaway.” If such a notation existed, its meaning would be profound—not because it created true equality, but because it shows how a planter could try to rewrite categories with a pen while keeping the underlying power imbalance intact.

Even if the precise ledger entry cannot be verified today, the idea reflects a real historical pattern: enslavers often documented human beings as inventory, and the language of recordkeeping shaped how communities justified coercion. A single line on a page could represent a life being reassigned, renamed, and constrained within someone else’s narrative.

The Record That Changed Everything

The most dramatic turn in the story involves an old birth record discovered during an audit of plantation papers. In this version, a misfiled document listed an infant named Eliza born to an enslaved woman, with the father’s identity indicated in a way that connected the child to Callaway himself.

If true, this would mean Callaway had entered a marriage without recognizing a direct family relationship—a revelation that would have been horrifying on every level, and one that would expose the darkest realities of slavery-era households: the blurred and hidden family lines created by exploitation and the routine denial of personhood.

It is important to describe this carefully. In the antebellum South, enslaved women had no meaningful legal protection, and “consent” as modern society defines it did not exist under coercion. Many family histories from that era contain painful, often unspoken legacies created by unequal power. A later-discovered record could shatter the public story a powerful man tried to tell about himself.

Silence Inside the Household

Oral histories frequently focus not on legal arguments but on the atmosphere that followed. In these accounts, the plantation household becomes quiet, tense, and watchful. Eliza is described as withdrawing emotionally, while Callaway is portrayed as unraveling under the weight of what the record implied.

Whether this “collapse” happened exactly as remembered is hard to prove. But the emotional logic is consistent: when a society depends on secrecy, the sudden presence of undeniable documentation—written proof—can destabilize the very person who benefited from silence.

Importantly, the enslaved community’s perspective is often the part most likely to be missing from official archives. Many stories preserved through later interviews stress that enslaved people frequently knew more than the official record acknowledged. They observed patterns, relationships, and unspoken truths within the plantation household, even when they were punished for speaking them aloud.

A Swamp, a Myth, and a Disappearance

Several versions of the story end with Callaway walking toward the swamp and never returning. Local officials, in later retellings, are said to have filed a simple report to close the matter—avoiding scandal, protecting the estate, and preserving the county’s image.

This too reflects an established pattern: when uncomfortable truths threatened powerful families, documentation was often minimized, misplaced, or deliberately sanitized.

Over time, folklore filled the gaps. The swamp became more than geography; it became a moral metaphor. Some residents later described strange sounds at night, or “humming,” turning the landscape into a kind of witness that never forgot what people tried to bury.

From a historical standpoint, such details should be treated as cultural memory rather than literal evidence. But cultural memory matters. It reveals what communities could not say directly, and what they needed symbols to express.

What Happened to Eliza

In the final section of many retellings, Eliza disappears from Mississippi and later reappears in a northern census record as a free woman with a trade. If that identification is accurate, it would be an extraordinary reversal of circumstances—one that underlines a broader truth: despite the machinery of slavery, many people pursued freedom through networks, migration, legal change, and sheer endurance.

Even without definitive confirmation of the specific census record, the idea fits a larger historical reality. Countless formerly enslaved people rebuilt lives in free states, often leaving behind few paper trails except those created by government enumerators and local churches.

Why This Story Still Matters

Whether every detail of the Callaway story can be proven is less important than what the narrative exposes about the world that produced it. Slavery created conditions where human relationships were distorted by ownership, where identity could be hidden or rewritten, and where the most vulnerable people were denied the ability to protect themselves or define their own lives.

It also shows how communities managed “reputation” by managing records. Erasure was not accidental. It was a strategy. Families burned papers, officials wrote evasive reports, and local society learned to look away.

If the story has endured for nearly two centuries, it is because it points to a broader lesson: power without accountability does not merely harm its victims. It corrodes everyone involved and leaves long shadows across generations. Some truths do not disappear when documents vanish. They survive in fragments, in memory, and in the uneasy feeling that a place can hold history even when a society refuses to name it.