In the spring of 1865, the United States stood at a hinge point. The Civil War was ending, slavery was being dismantled in law, and a new era—fragile, contested, and often dangerous—was beginning in practice. It was a time when millions of newly freed families tried to build lives with little protection and fewer guarantees, while old power structures fought to reassert themselves under new names.

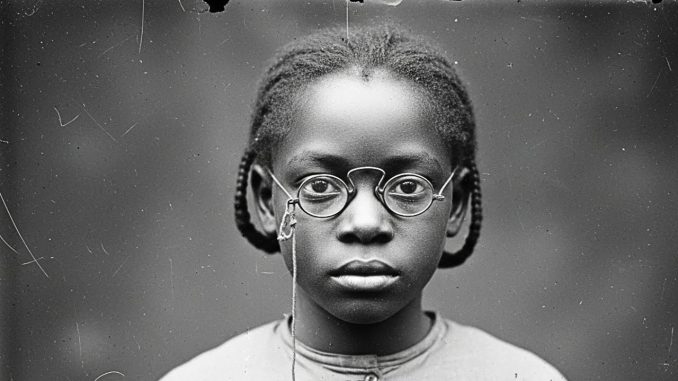

It’s within this uncertain landscape that some local accounts place the story of Sarah Brown, a Black child in rural Georgia said to have possessed an unusually strong ability to recall information after a brief glance or a single hearing. Today, people might label such an ability as “eidetic memory,” though the term is debated and the science of memory is more complicated than any one phrase suggests. Still, the idea behind Sarah’s story is clear: in a world determined to control what could be learned, what could be recorded, and what could be acknowledged, a child who remembered details with striking accuracy could become both admired and feared.

As with many stories from the Reconstruction era—especially those involving Black children, rural communities, and informal schooling—the historical record is uneven. Some versions rely on oral history, church correspondence, and later recollections that may not align perfectly. What can be responsibly said is this: the story reflects real conditions of the time, including the hunger for education, the vulnerability of Black families, and the pressures placed on anyone who challenged prevailing beliefs about Black intelligence and potential.

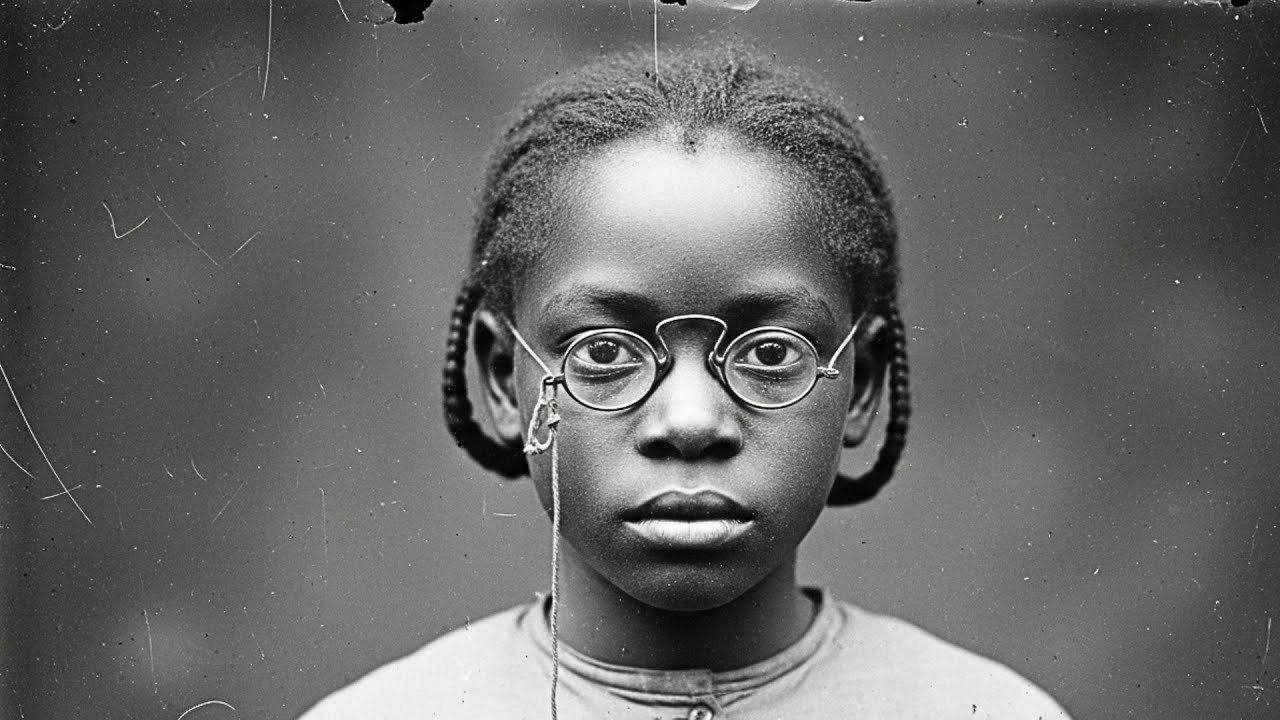

Sarah is often described as being born around 1858 in Wilkes County, Georgia, where small plantations and farms were tied into the wartime economy. Her mother, Harriet, is portrayed as a domestic worker who moved through the “main house” and the work areas, navigating a daily life shaped by exhaustion, constant risk, and an awareness that safety could change from one hour to the next. In many retellings, Sarah’s father is absent from the record, which was common in enslaved communities where legal recognition of family structures was routinely denied.

After emancipation, Harriet is said to have taken Sarah into a nearby town where newly freed families clustered around churches, mutual aid networks, and the earliest efforts at organized schooling. The promise of education was not abstract. For families who had been punished for reading and writing, a classroom—no matter how small or under-resourced—could represent dignity, future income, protection, and the power to navigate a world that ran on paperwork.

One account places Sarah in a makeshift school held in a church building. The teacher is often named as Martha Williams, described as a young Black educator connected to northern religious networks that supported freedpeople’s education. The classes, in this telling, were crowded and mixed-age: children learning letters beside adults learning to sign their names. Supplies were scarce. Light was limited. The atmosphere combined fatigue with determination.

Sarah, the story says, stood out quickly. She learned the alphabet at remarkable speed, copied shapes and spacing precisely, and repeated short passages after hearing them once. When shown a page, she could describe not only the words but where they sat on the page—what was near the top, what was near the middle, what line a phrase appeared on. Whether every detail of these descriptions is literal or partly stylized through retelling, the underlying point is consistent: Sarah’s learning appeared unusually fast and unusually accurate for her age.

Within her community, that kind of ability would have brought pride, but also worry. In the Reconstruction South, education itself was often treated as a provocation. A child with conspicuous skill could draw attention to a family that had little protection. So many versions of the story emphasize caution: adults urging discretion, teachers warning parents, neighbors advising Harriet to keep Sarah’s abilities from becoming a public spectacle.

The narrative then introduces a second force: outside curiosity. In some retellings, a doctor or official visitor—sometimes described as connected to federal relief or medical work—observes Sarah’s abilities and begins testing her with pages, numbers, diagrams, and lists. The tests are described as relentless, less like teaching and more like measuring. This is where the story shifts from “gift” to “burden,” illustrating how Black talent could be treated as something to be used rather than nurtured.

A particularly troubling element in the accounts is the suggestion that Sarah was displayed in public demonstrations—invited or pressured to perform her memory skills for paying audiences. It is important to handle this carefully: entertainment practices in the 1860s were often exploitative, and Black performers, especially children, were vulnerable to coercion and manipulation. Whether Sarah’s case occurred exactly as described or reflects a composite of common abuses, the idea is historically plausible. Black bodies and Black talent were routinely commodified, and the boundary between “curiosity,” “education,” and exploitation was frequently crossed.

The story reaches a turning point when Sarah’s memory intersects with local reputations. In one frequently repeated version, she is handed a newspaper clipping or printed report about a past incident from the war years. After reading it briefly, she repeats it with unusual precision. Then she recognizes names and faces connected to it—men she has seen in town, men with status. The room changes. Admiration becomes unease. People realize that memory is not only a party trick. It can be a mirror.

This is the heart of why Sarah’s story has endured in the way it has. It’s not really about supernatural ability. It’s about the fear of documentation and recall in a society built on selective memory. Reconstruction was not only a fight over laws and elections; it was a fight over whose stories would be believed, whose suffering would be acknowledged, and whose actions would be forgotten. In that environment, a person who remembered names, dates, and details could disrupt the comfort of those relying on ambiguity.

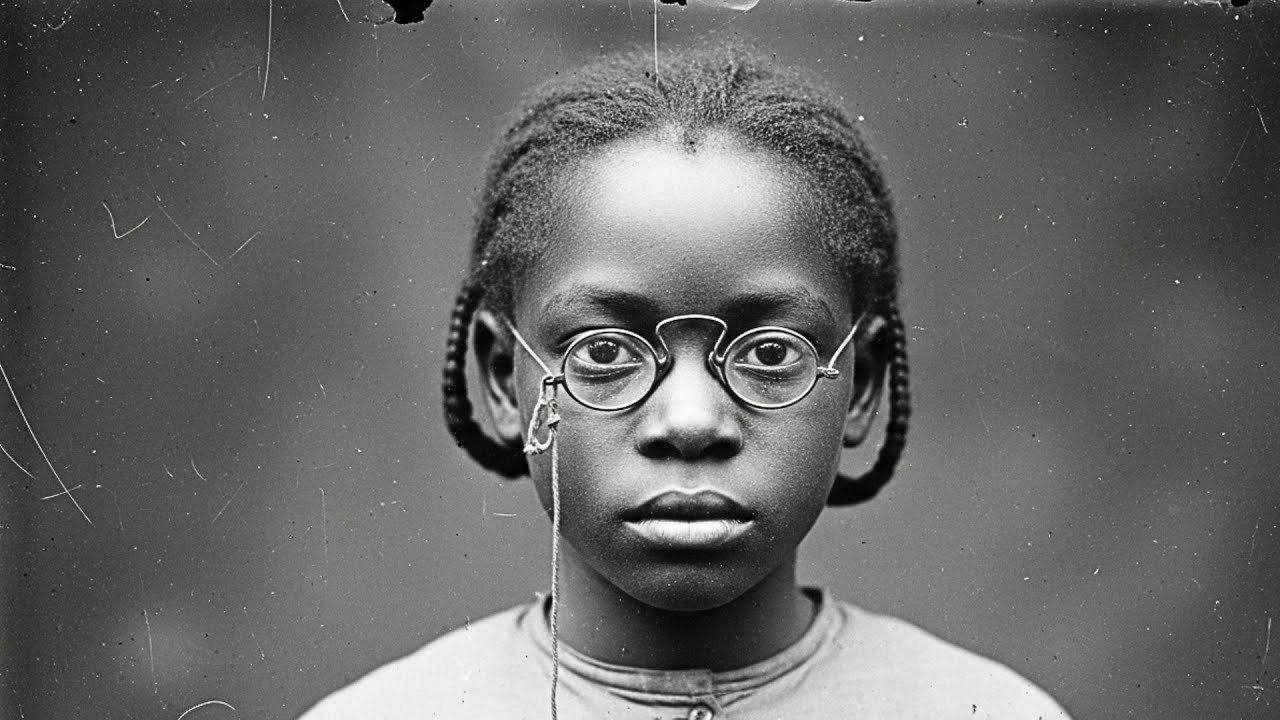

After this moment, the story often describes a sudden closing of doors. Public demonstrations stop. Mentors disappear. Papers go missing. The people around Sarah become quiet, cautious, and protective. Harriet, the mother, is typically portrayed as realizing that her daughter’s safety depends on leaving—moving to a larger city, seeking a stronger community network, and staying under the radar.

In many versions, they move to Augusta, where churches and mutual aid societies offered more support than smaller towns could. There, Sarah is said to have been guided by clergy and educators who saw her ability not as entertainment but as service. She becomes, in the telling, a living archive. Families share names, old letters, faded photographs, stories of relatives separated by forced sales, and the little fragments that might help them rebuild their family histories. Sarah listens, remembers, and repeats details back when needed—helping people hold onto information in a world where official records often excluded them.

This section carries a quieter kind of tragedy: a child being entrusted with the weight of adult grief. Even without dramatic scenes, the emotional load would have been immense. Memory, in such a life, would not be a simple advantage. It would be a responsibility that followed her into sleep, into school, into adulthood.

The later chapters of the story, depending on the version, suggest that Sarah was eventually sent north to study—sometimes to Philadelphia—supported by church networks. She reportedly excelled in languages, mathematics, and history, astonishing teachers with the speed and accuracy of her recall. Yet she also struggled with what she could not “turn off.” The same skill that helped her learn could also keep painful experiences vivid.

Then, as many tellings conclude, Sarah disappears from the record in the late 1870s. No clear marriage record. No definitive employment record. No confirmed grave. Some accounts propose she changed her name to protect herself. Others suggest illness, exhaustion, or institutionalization—outcomes tragically common for vulnerable people in a period with limited medical understanding and minimal social protection. With incomplete documentation, certainty is impossible.

What remains is the symbolic truth her story points toward: Black brilliance existed everywhere, including in children, and it was routinely constrained by poverty, exploitation, and fear. Sarah Brown—whether understood as a single historical figure with an incomplete paper trail, or as a story shaped by many similar lives—forces a question that still matters now.

What happens when a society treats intelligence in a Black child as something to control rather than cultivate?

If the world around Sarah had been different—if she had been protected, resourced, and encouraged—she might have become a scholar, a teacher, a writer, a leader in a field that needed sharp minds. Instead, the story insists that her gift was treated as risk, and the safest path offered to her was quietness.

In the end, Sarah Brown’s legacy is not only the idea of extraordinary memory. It is the reminder that memory itself—accurate, persistent, unflinching—can challenge comfortable narratives. It can protect families from being erased. It can preserve truths that official books ignore.

And perhaps that is why stories like hers keep returning, even when the archive is thin: because they speak to a deeper reality. Nations are built not only on what they record, but on what they try to forget. A child who remembers, in that kind of world, becomes more than a prodigy.

She becomes a witness.